This post is the text and images from a book chapter that I have recently had published. The published version has had the images converted to black and white, so I thought I’d post the proper version here, as I still hold the copyright for the chapter and it works better with colour imagery. This is the bibliographic reference if you want to cite me or find the rest of the book, which is a very interesting read indeed (no claims made of the same for what follows!):

Green, C. 2019. “Cartography and Quantum Theory: in defence of distribution mapping.” In: M. Gillings, P. Hacigüzeller, G. Lock (eds.) Re-mapping Archaeology: Critical Perspectives, Alternative Mappings. Abingdon: Routledge, 281-299. ISBN: 978-1-138-57713-8

Endnotes have been included after the paragraph in which they are referenced, rather than at the end of the text.

13 Cartography and Quantum Theory

In Defence of Distribution Mapping

Christopher Green

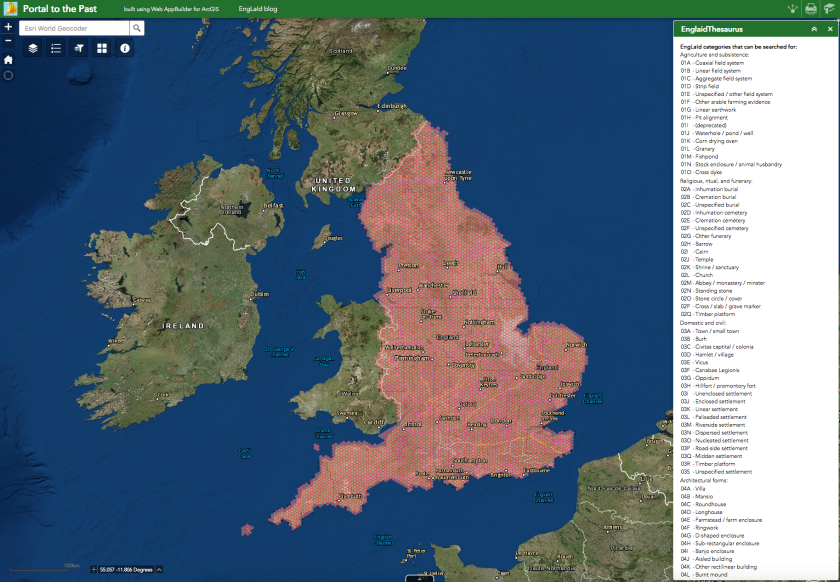

Distribution Mapping in Archaeology: a Perceived Problem

This paper was written whilst working on the English Landscapes and Identities Project (EngLaId) at the University of Oxford. During my time working on EngLaId, I have been confronted with two things: my own improvement as a cartographer (by which I mean a maker of maps) over a substantial period of my life (see below); and how to gestate years of experience into guidelines for the somewhat less practiced members of the project team, employed to work with GIS and maps on an almost daily basis but mostly with little formal cartographic training. Alongside the rest of the project team, I have also spent a great deal of time pondering how to present the extremely complex and characterful data of the project to academic and public audiences (Green 2013; Cooper & Green 2016): the main EngLaId database contains over 900,000 records of English archaeological remains from the Middle Bronze Age (c.1500BC) to the end of the early medieval period (c.AD1000), including an almost unquantifiable large element of duplication due to its origin in a multiplicity of source datasets. Turning this complexity into a series of comprehensible messages is a difficult task (Green et al. 2017).

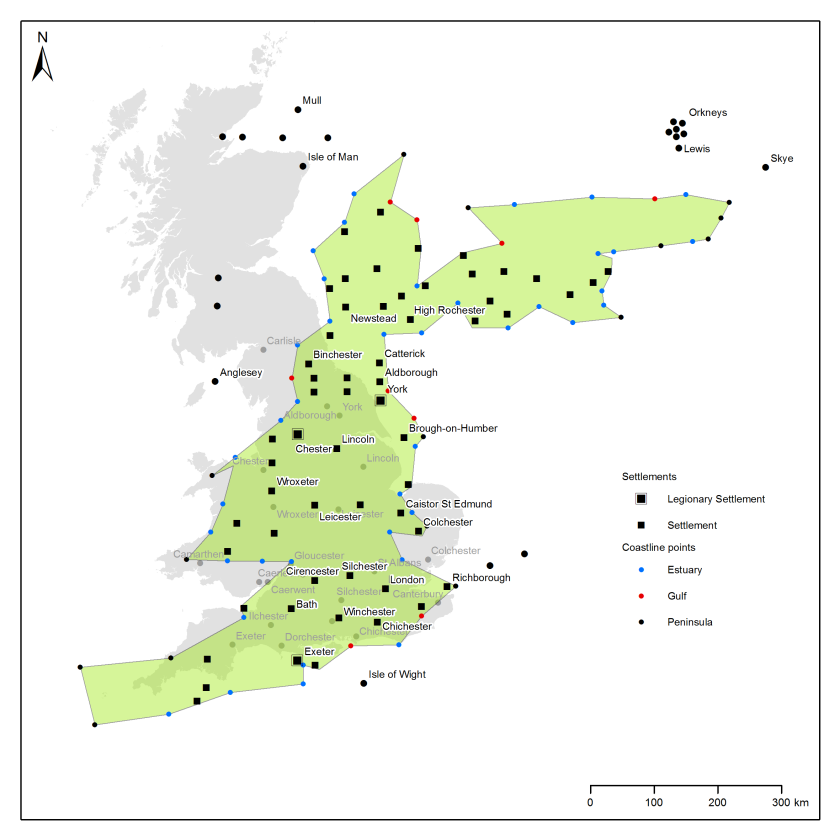

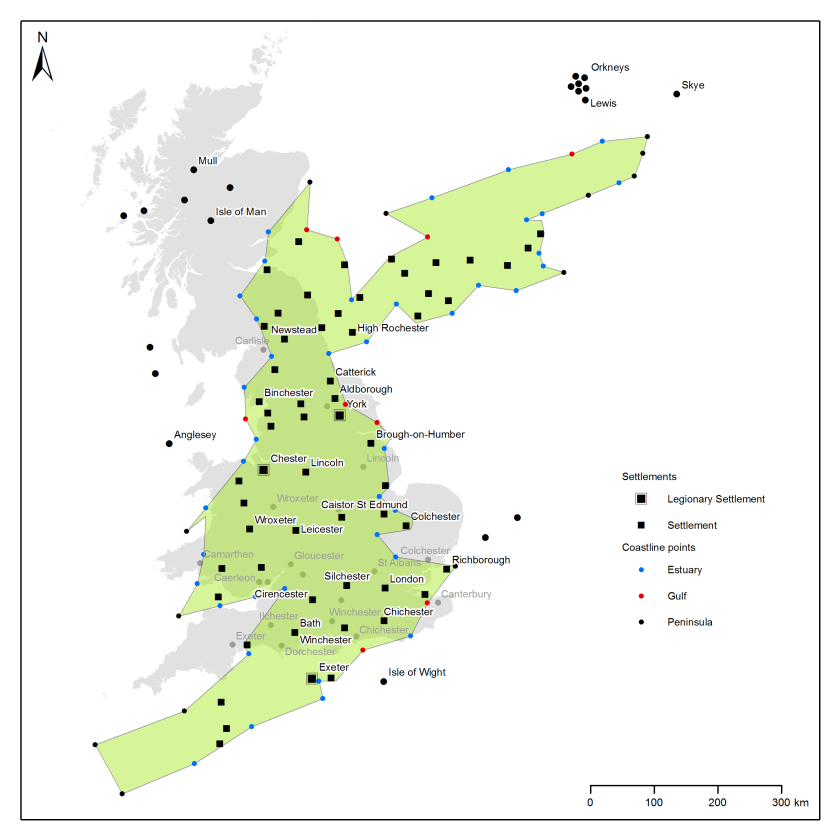

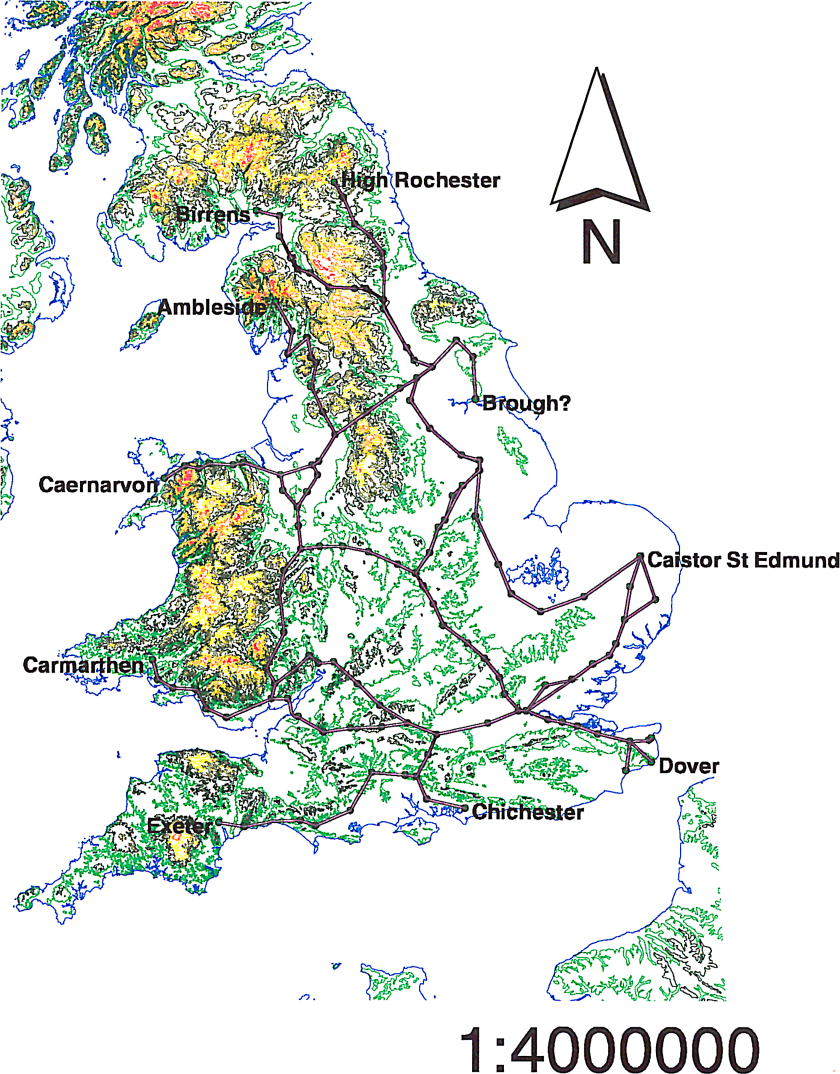

If we ignore a childhood spent doodling maps of imagined lands, my first real experience of formal cartography came as an undergraduate archaeology student at the University of Durham. As I would imagine is the case with many archaeologists (and indeed many geographers), I first encountered GIS as a map making tool (obviously it is also much more, but this paper only considers the cartographic aspects of GIS) as part of a course on computers and computing in archaeology. I recall little formal teaching on good map design, and maps that I subsequently made for my dissertation, which was an attempt to construct a “mental geography” of Roman Britain, show a considerable cartographic naivety (Figure 13.1): amongst several errors, note the excessively large north arrow and the use of a fractional scale for a map which would inevitably be resized in the final document (thus making the scale incorrect, as it also is here).

Fig. 13.1: Map created by the author in 1999 as part of his undergraduate dissertation. The lines depict routes in the Antonine Itinerary (after Rivet & Smith 1979).

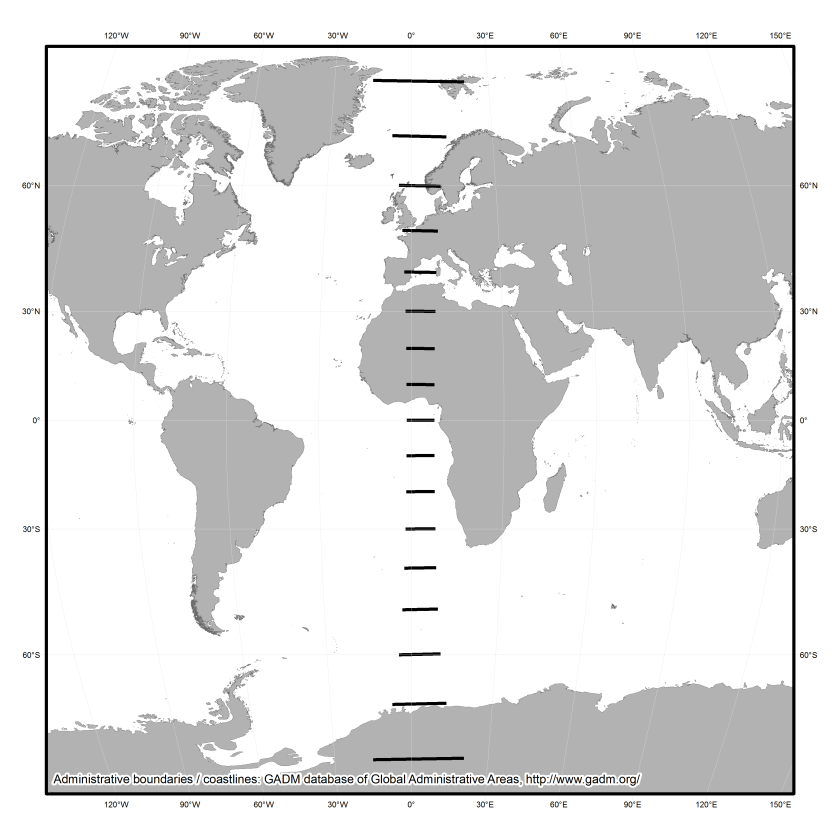

This, then, is the situation in which many archaeologists find themselves: forced to make maps as part of their projects or employment, but with little expertise in what we might call good cartographic practice and with little opportunity to learn other than through trial, error, and repeated effort, especially in the academic sector (more structured training and formal cartographic guidelines may be provided in the commercial sector – Victoria Donnelly, pers. comm.). One consequence of this is the mistaken orthodoxy of certain prescribed practices, such as “a map should always have a scale bar” (Wood 2003: 7): many commonly used map projections (including the still very widely used modern derivatives of Mercator) do not preserve distances and so adding a scale bar to a map of large areas of Earth created in such a projection is simply incorrect (as measured distance will vary across the map) (Figure 13.2).

Fig. 13.2: Map of the world rendered in the very commonly used “WGS84” projection setting in ArcMap. Thick black lines are of 1000km length illustrating the incorrectness of adding a scale bar to such a map (or at least just a single one). Contains data derived from the GADM Database of Administrative Areas (http://www.gadm.org/).

Another consequence of cartographic naivety is the widely heard verbal (albeit rare in print) complaint that mapping distributions is “just putting dots on maps”. Although it may often be correct to say that dots can be a poor way of representing extended areas of past settlement (Evans 2000: 3), that is essentially a question of the scale at which one works. Scale is, in fact, key herein and we shall return to the issue later. One form of distribution mapping for which complaints of being “just dots on maps” are somewhat justifiable are the very common phenomenon of “sites referred to in the text” (another mistaken orthodoxy), at least where no spatial context is given beyond a coastline and perhaps major rivers. Without sufficient context (an issue we shall return to below), such maps are largely without merit, as they will be of little practical use to readers who do not already possess a strong knowledge of the geography of the area mapped: a gazetteer with grid references would be far more useful if a reader wished to subject results to further data analysis. At the very least, a distribution of all sites of the same type should be included, rather than simply those chosen by the author to write about: without that, any conclusions drawn by a reader (or the author) regarding the distribution of the sites discussed will be entirely meaningless.

In part, criticism of distribution mapping arises out of the wider phenomenon of postmodern critique, specifically seen in archaeology in the tension between so-called phenomenological and Cartesian approaches (Sturt 2006: 121): maps are seen as a tool of positivism, providing a restricting and classificatory top-down perspective at odds with lived experience on the ground in the real world. Yet the recovery of lived experience of the past is an impossible dream. Crampton states that there is, to the postmodern eye, something unseemly about maps (2010: 6):

“These wretched unreconstructed things seem to work so unreasonably well! [original emphasis]”

Crampton accepts that maps enabled many abhorrent elements of the modern age, such as colonialism, racism, warfare, espionage, and that GIS is seen by some as a Trojan Horse for the return of positivism. Yet he states that this is not exclusively true of maps but also of many other things. Like the power of the atom, maps can be used for beneficial as well as unfortunate purposes (Crampton 2010: 6–7). Maps in and of themselves, then, are not part of the problem: how we use them and how we construct them are the real issues. Making a map involves an inevitable task of classification and simplification of real world phenomena, but this can as easily be approached as a subversive act as it can as an act designed to promote an imperialist (whether colonial or economic) agenda.

Map Making in a Digital World

Through the 20th and early 21st centuries, the practice of making maps (alongside GIS generally) became increasingly divorced from both geography and cartography as academic subjects, to the extent that people who never made maps (e.g. lecturers) could claim to be cartographers (Crampton 2010: 2). Conversely, it is now possible for any person with a computer and access to the internet to make a map: cartography as a practice has opened up to the public and escaped from its academic confines, aided by practices such as “map hacking” and “mash-ups” (Gartner 2009) and software such as Google Earth (Collins 2013). However, this democratisation is highly dependent upon access to computers and information technology expertise (Crampton & Krygier 2006: 12, 18–19; Field & Demaj 2012: 70). Today, the use of maps and spatial technologies has never been more common and more widespread (Crampton 2010: 11), immanent in the continually strengthening “geo-lifestyle” revolution (Field 2009: 59).

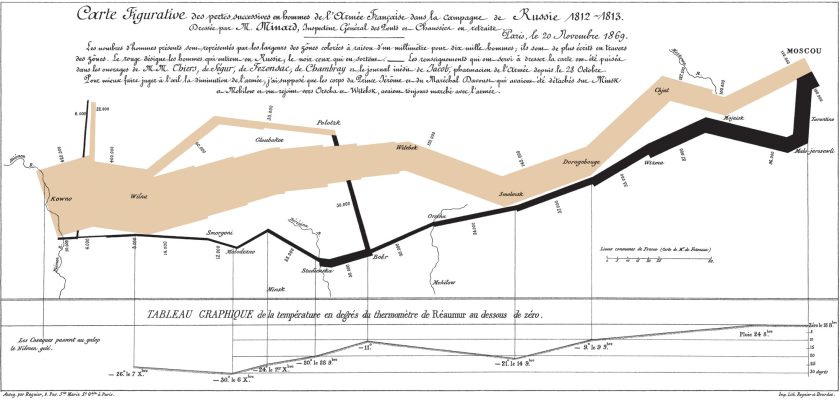

Some celebrate what they see as the death of cartography as an academic subject (see Wood 2003 for a wonderful polemic on the question), although as a practice it has never been healthier (Crampton 2010: 24). Academic journals on the subject and on GIS more widely are now largely dominated by technical issues rather than the aesthetic or the political (Crampton 2010: 5), whereas the people actually making maps have changed, now including data artists, journalists, and coders. Non-cartographers have always made fine maps from time to time (e.g. Harry Beck’s Tube map, Charles Minard’s map of the advance of Napoleon into Russia [Figure 13.3], or John Snow’s epidemiological map of cholera in London), but the world is now awash with maps made by untrained map makers (Field 2015: 93). This should be seen in a positive light, with cartography as a practice slipping from control of the elites who have dominated it for centuries (Crampton 2010: 40) in what Field drolly calls (2014: 1):

“…a cacophony of cartography… a harsh, often discordant mixture of the weird and the wonderful.”

Fig. 13.3: Charles Minard’s 1869 map of Napoleon’s Russian campaign of 1812–3, showing the successive losses of soldiers along the route. This is a public domain image obtained via Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Minard.png).

The reaction within the academic fields of cartography and GIS to democratisation of cartographic practice has been less positive in many cases. Professions with power organise and force through legislation to protect their positions (e.g. law or medicine), whereas weaker professions create certification criteria and denigrate the output of non-professional rivals (Wood 2003: 5). Cartography and GIS fall into the latter category, as seen in the existence of the GIS Certification Institute in the USA (Crampton 2010: 36). This rather parallels the role of the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists[1] (CIfA) in British archaeology: like archaeologists, any person can now claim to be a cartographer, which some find discomfiting. Systems of ethics (Dent et al. 2009) and guidelines (Southworth & Southworth 1982) for “good” map design exist (MacEachren 1995; Monmonier 1996; also Tufte 2001 for data visualisation more widely), but are largely ignored by untrained makers of maps, causing professional cartographers to call for a return to best practice (Field 2005; 2014; Kent 2005: 187).

[1] CIfA is a membership organisation which requires the provision of references and work samples to become an accredited member, and which involves members signing up to a code of conduct, etc. See: http://www.archaeologists.net/

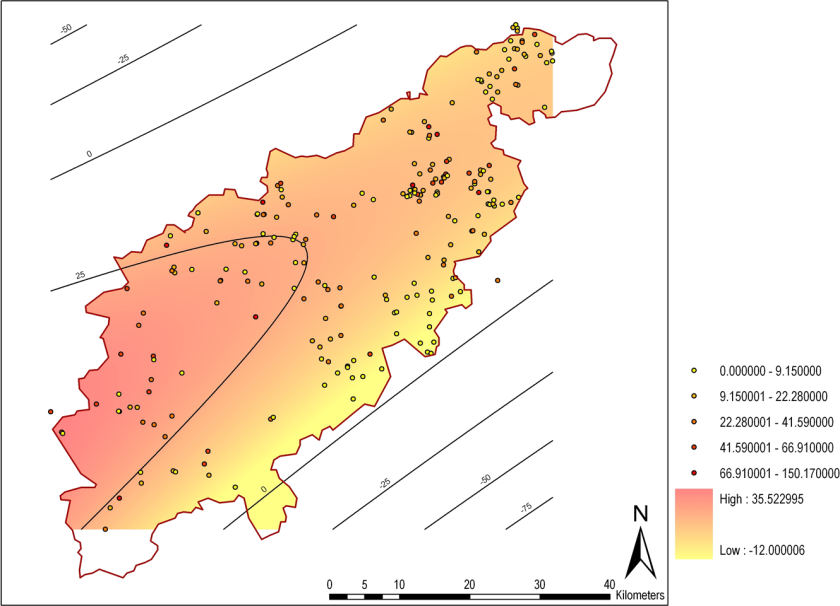

To return to the example of my own career, from 2001 to 2002 I studied for an MSc in GIS within a geography department. There, I learned a great deal more about GIS and about making maps (including cartography taught as visualisation – Field 2005: 81). However, the great majority of my peers had been through the undergraduate geography degree and, as such, certain key concepts were not covered in a great deal of detail (particularly map projections). In 2005, I commenced a PhD looking at the representation of time in archaeological GIS (published as Green 2011). In the course of that piece of work, I made a great many more maps and my cartographic skills improved (Figure 13.4). However, I still made mistakes, albeit ones that might be less apparent at first glance: in Figure 13.4, note the division of the first four sections of the scale bar into 2.5km units (five 2km units would perhaps be more logical) and the spurious precision of the values in the legend. I also dislike the ArcMap default American spelling of “Kilometers”. Furthermore, it would have been better to extend the extent of the trend surface to the full bounds of the county so that there were no white areas within the boundary polygon.

Fig. 13.4: Map created by the author in 2008 for his PhD thesis (later published as Green 2011). The trend surface shows a model of pottery deposition in Northamptonshire between AD115 and 240. This image contains data derived from Jeremy Taylor’s unpublished PhD thesis, originally gathered by David Hall.

The point of this autobiographical example is that even with training and practice, those engaged in map production may still make mistakes, which in some cases might confuse the message being communicated. They may sometimes only be obvious to experienced cartographers, but the key message here is that no map can ever be perfected to the taste of all audiences. Those without formal training in cartography might make more mistakes or produce maps that fail to please the cartographic profession, but their ability to produce new insights should be embraced. It is clearly not possible, nor probably desirable, to provide cartographic training to every person who now wishes to make a map, but some form of guidance is needed if people are to produce comprehensible output. For that guidance, we can find inspiration in what is perhaps an unlikely arena: quantum theory.

The Uncertainty Principle

The Uncertainty Principle, formulated by Heisenberg (1927), forms one of the foundational elements of the field of quantum mechanics. Hawking described its effects eloquently (2011: 62-63):

“In order to predict the future position and velocity of a particle, one has to be able to measure its present position and velocity accurately. The obvious way to do this is to shine light on the particle. Some of the waves of light will be scattered by the particle and this will indicate its position. However, one will not be able to determine the position of the particle more accurately than the distance between the wave crests of light, so one needs to use light of a short wavelength in order to measure the position of the particle precisely. Now… one cannot use an arbitrarily small amount of light; one has to use at least one quantum. This quantum will disturb the particle and change its velocity in a way that cannot be predicted. Moreover, the more accurately one measures the position, the shorter the wavelength of light that one needs and hence the higher the energy of a single quantum. So the velocity of the particle will be disturbed by a larger amount. In other words, the more accurately you try to measure the position of the particle, the less accurately you can measure its speed, and vice versa. Heisenberg showed that the uncertainty in the position of the particle times the uncertainty in its velocity can never be smaller than a certain quantity, which is known as Planck’s constant. Moreover, this limit does not depend on the way in which one tries to measure the position or velocity of the particle, or on the type of particle: Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle is a fundamental, inescapable property of the world.” [my emphasis]

The useful part of this for our purposes here is the idea that the greater the precision one can discover about one aspect of a particle’s state, the lesser the precision that one is able to discover about another (related) aspect of said particle’s state. This appears to be a fundamental property of the universe that we exist within. Whilst I would not propose the existence of a Planck’s constant for cartography, the idea that precision of measurement on one variable is related to precision of measurement in another variable can form a very useful metaphor for the untrained cartographer for estimating the level of detail that can be comprehensibly placed upon a map, with the “particle” being equivalent to any element placed on a map.[2]

[2] Incidentally, knowledge of Heisenberg has previously been suggested as a desirable trait for archaeologists, albeit as a metaphor for greater archaeological understanding of the natural sciences rather than anything specifically to do with Heisenberg’s work (Pollard 1995). One might also get a sense of the Uncertainty Principle in Olivier’s Cycles of Memory (2011: 190–194) and certainly in his uncertainty principle of the archaeological past, in which he states that it is impossible to know both the position of any moment of the past in time (i.e. its date) and its rate of transformation (i.e. its place in evolutionary history) (Olivier 2001: 69).

Using the Uncertainty Principle to Understand Archaeological Cartography

Time (usually as date or period), space (usually as place of discovery), and type (often as typological category) are fundamental to the nature of archaeological data. Time and type have been extensively theorised within archaeology, but space arguably less so, with most theoretical considerations of space in archaeology focusing on ontological questions (e.g. space as an a priori container) rather than epistemological ones. Key to the epistemological theorisation of space is spatial scale, with different past processes potentially discernable at different scales (Wheatley 2000: 123, 128; Lock & Molyneaux 2006b: 1; papers in Lock & Molyneaux 2006a, particularly Yarrow 2006).[3]

[3] The terms “large” and “small” are problematic when applied to spatial scale due to the differing conceptions of cartographers (who use “large” to mean a large representative fraction, e.g. 1:10,000, and “small” to mean a small representative fraction, e.g. 1:250,000) and most other people (who would expect a “large” scale analysis to cover a large amount of space, and vice versa) (Lock & Molyneaux 2006b: 5). As such, herein I will use the terms “narrow” to refer to spatial scales that cover smaller amounts of space in higher detail and “broad” to refer to spatial scales that cover larger amounts of space at lower detail.

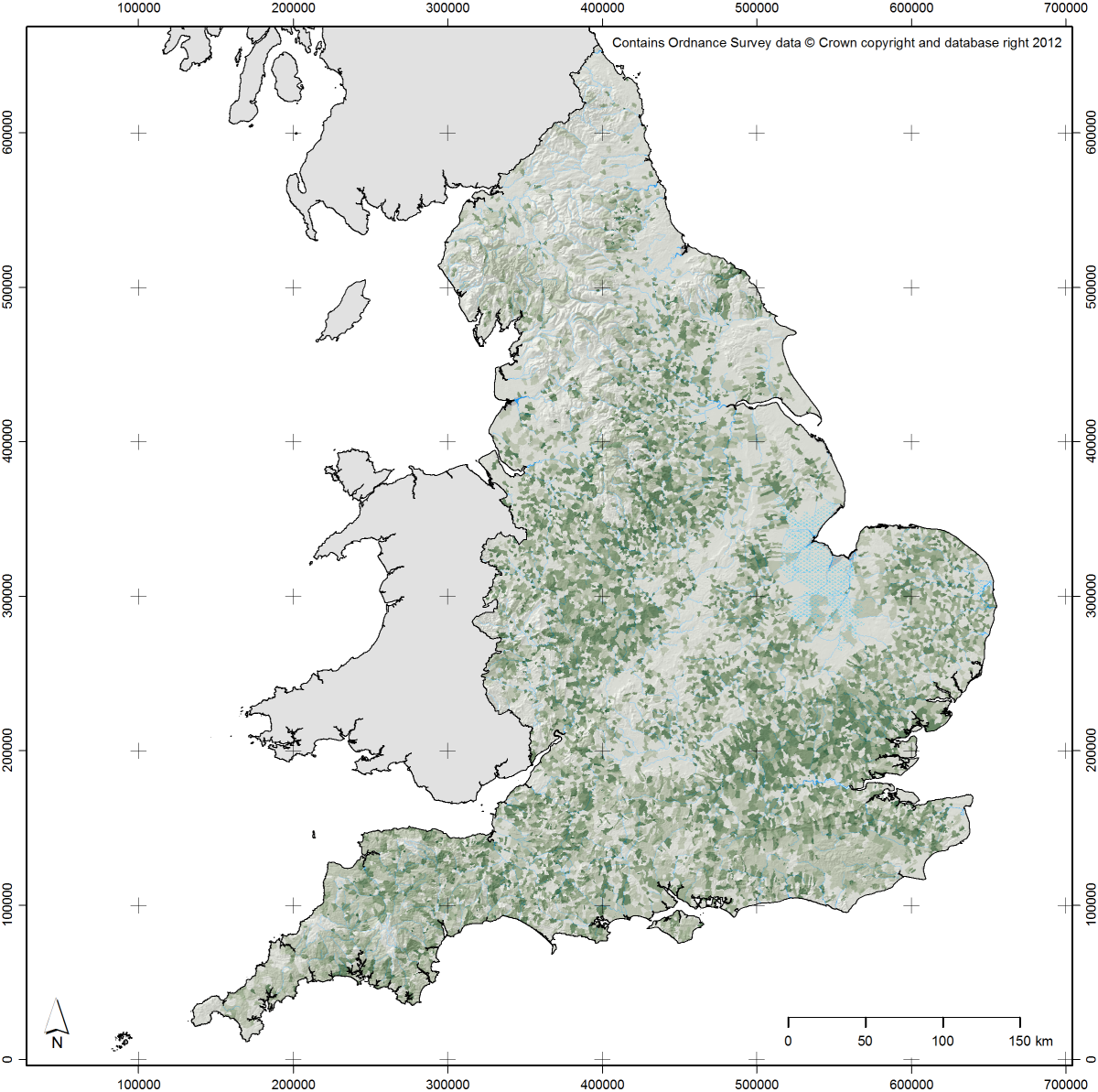

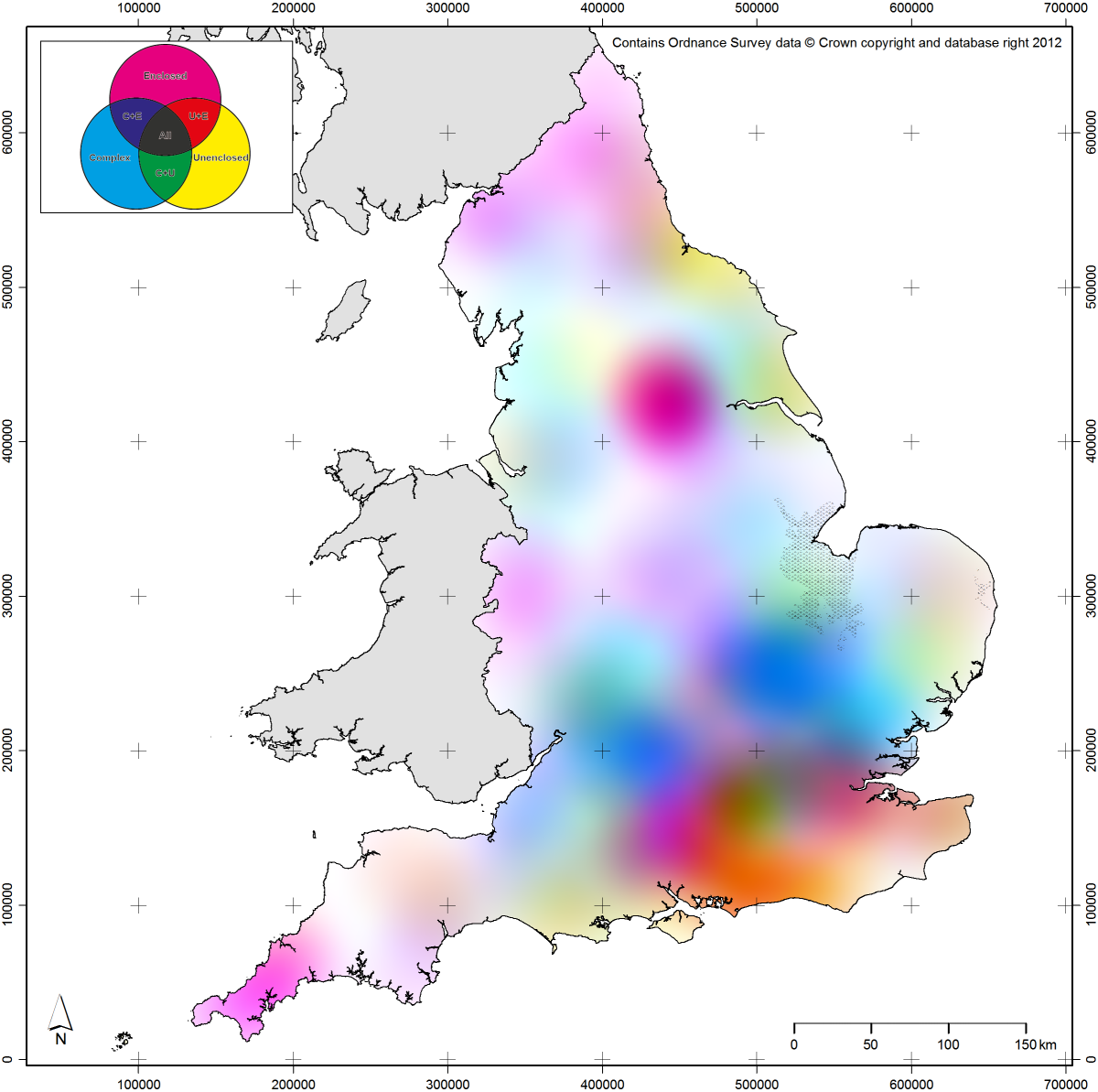

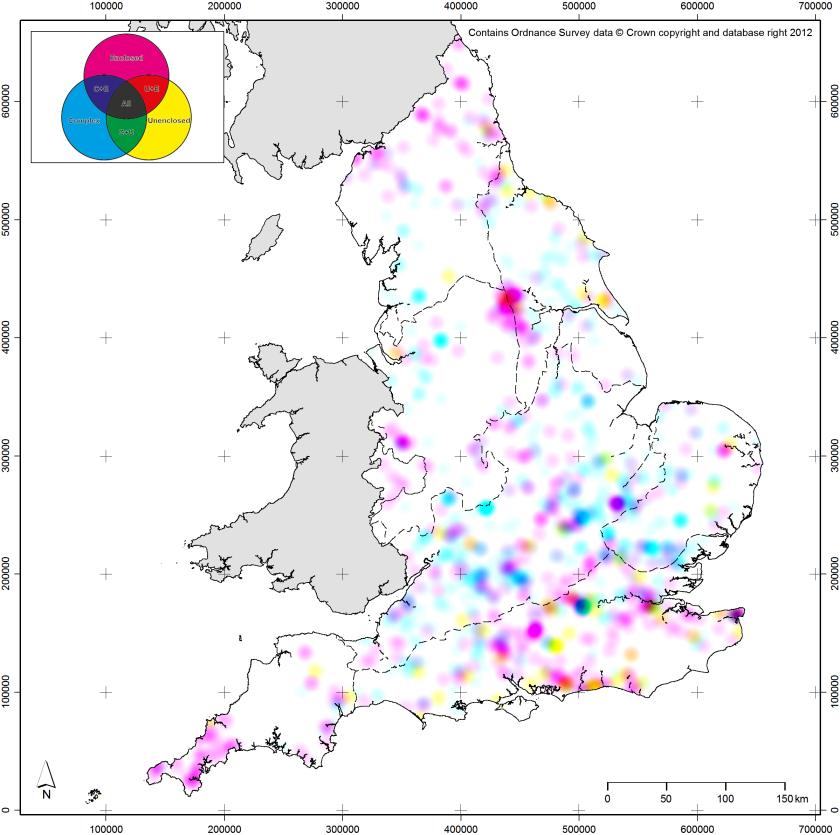

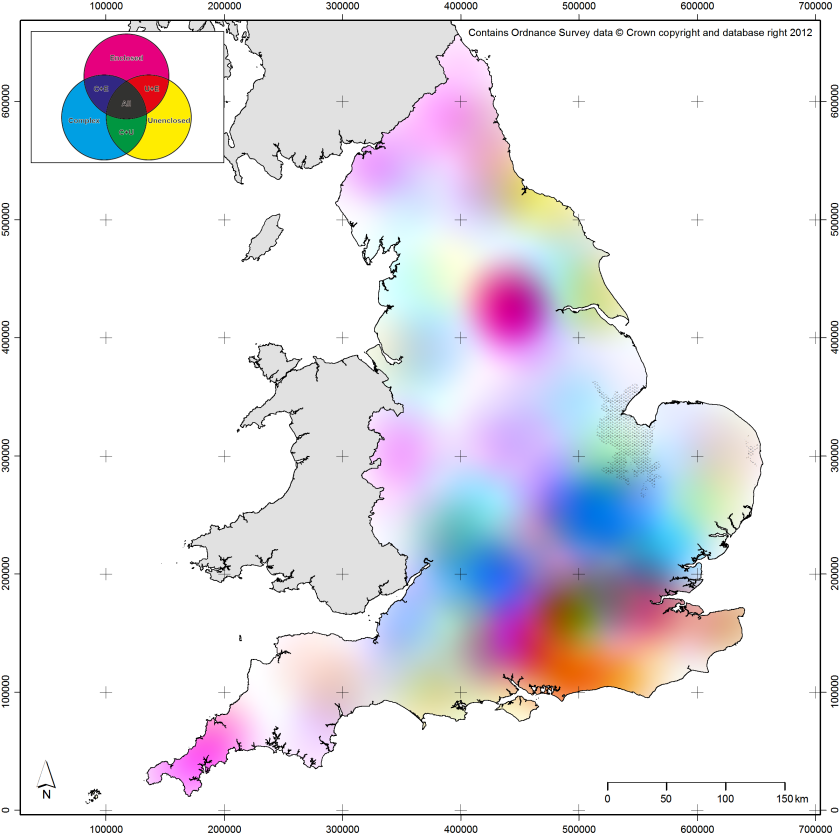

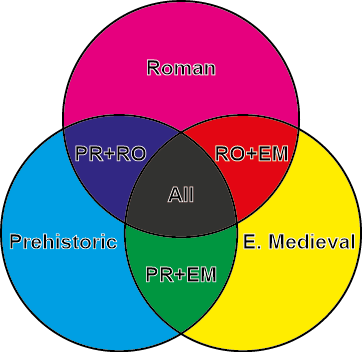

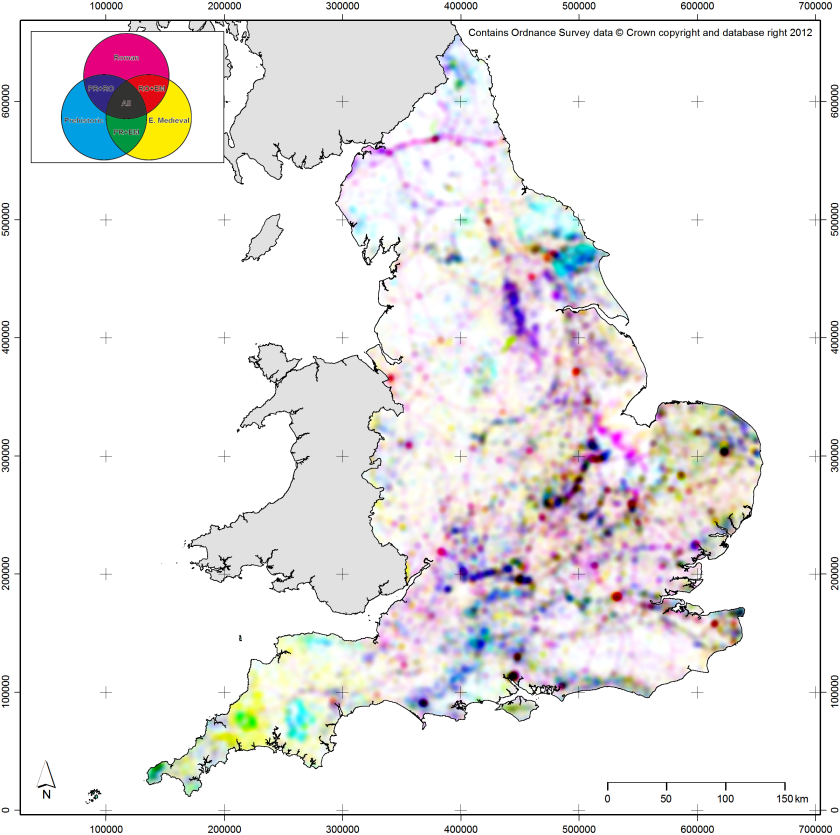

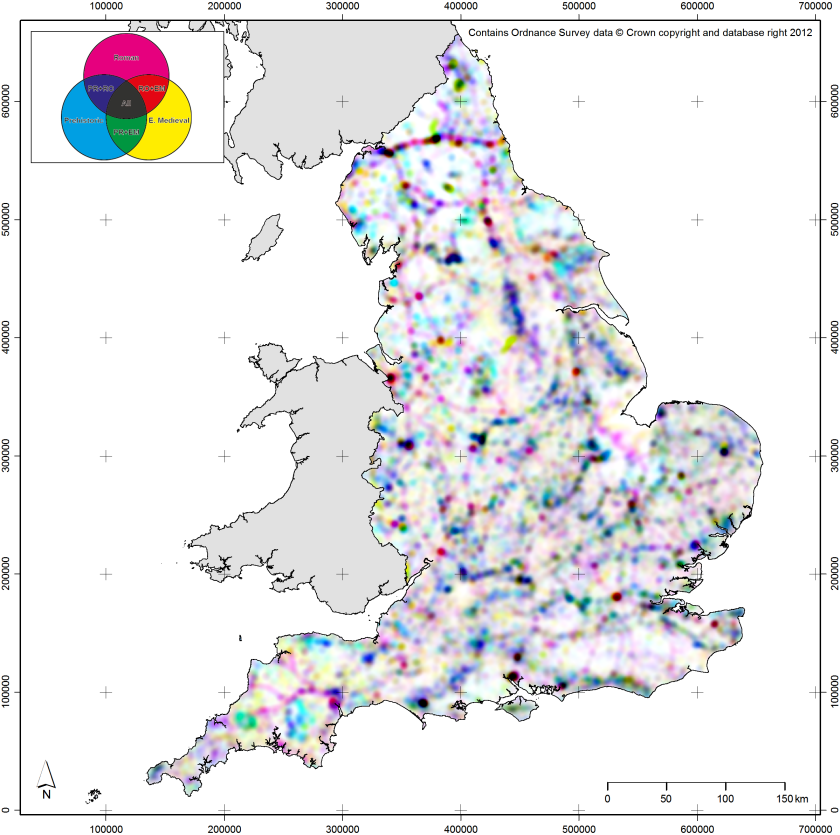

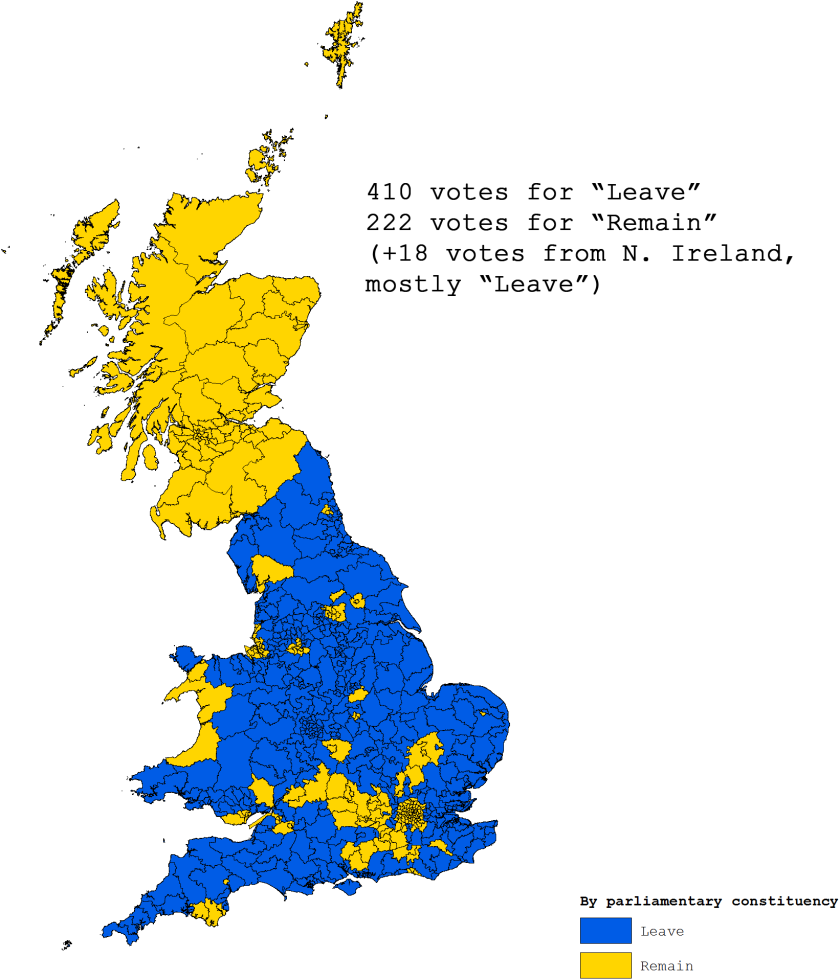

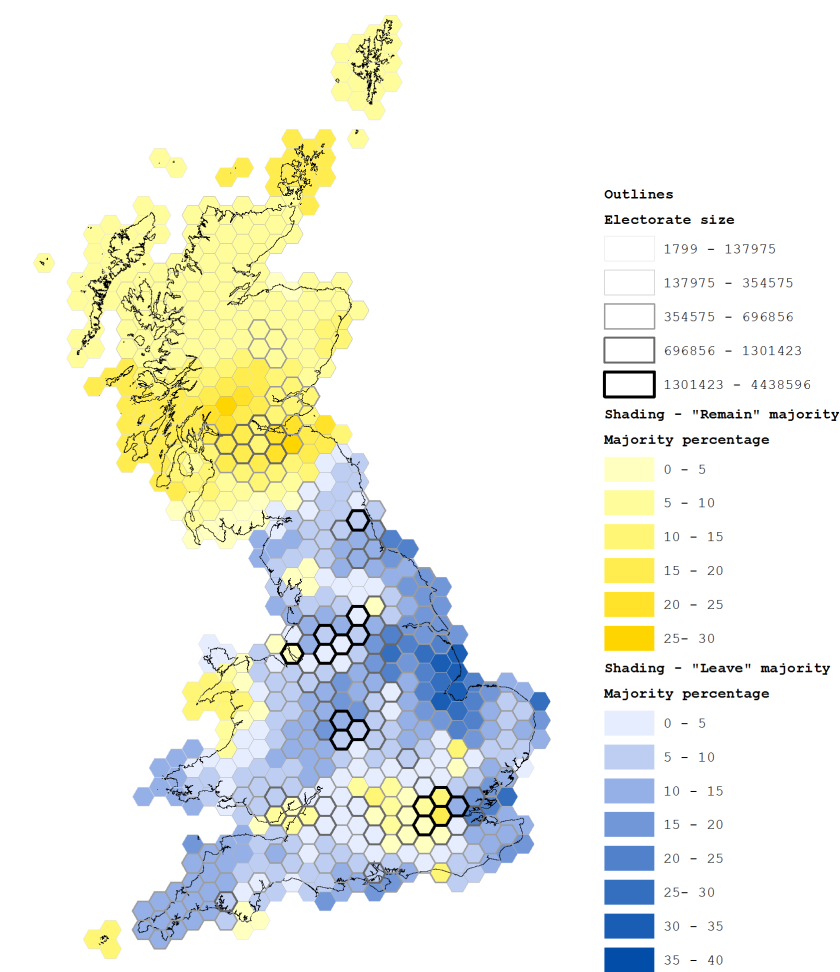

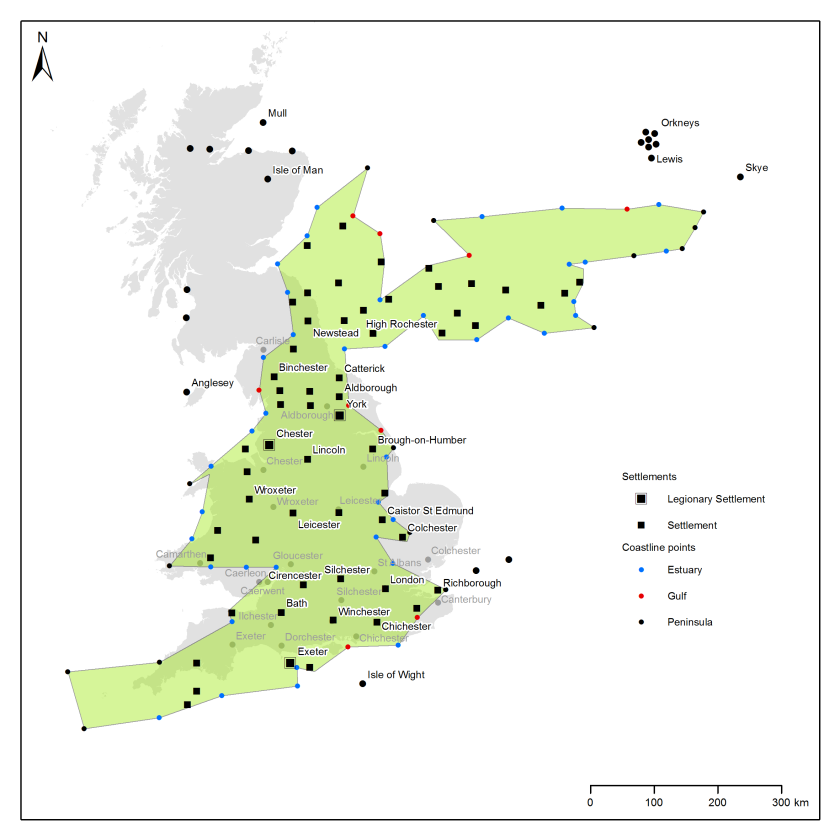

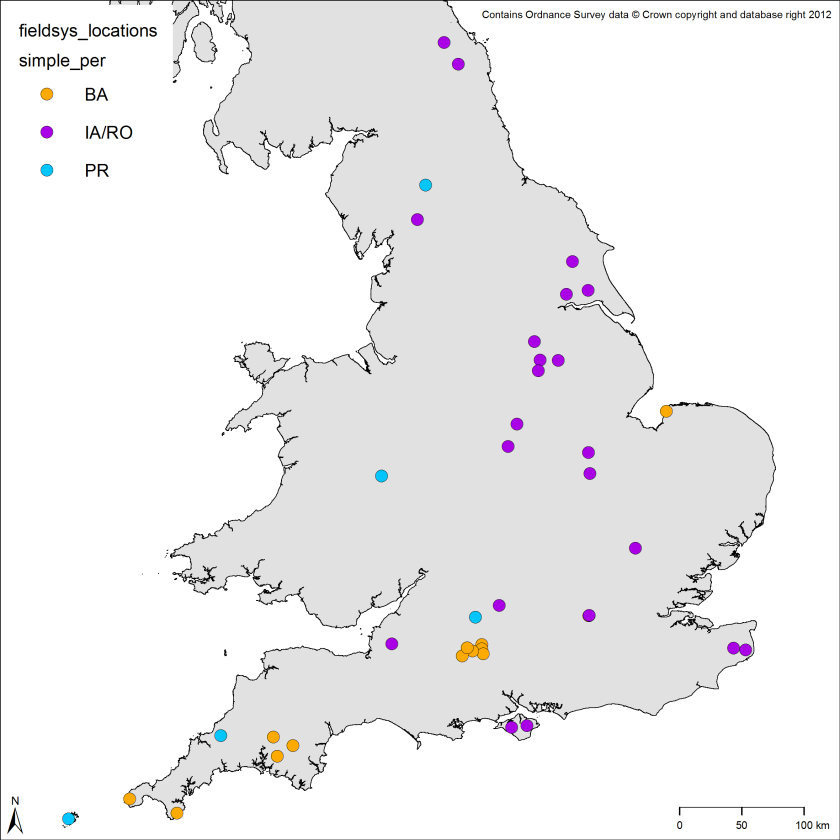

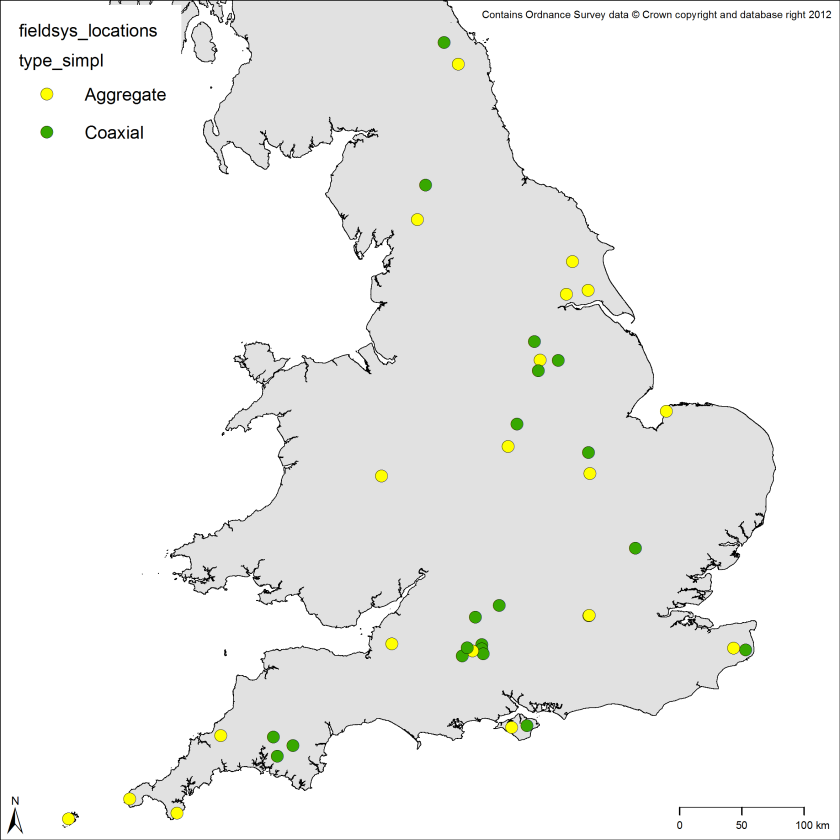

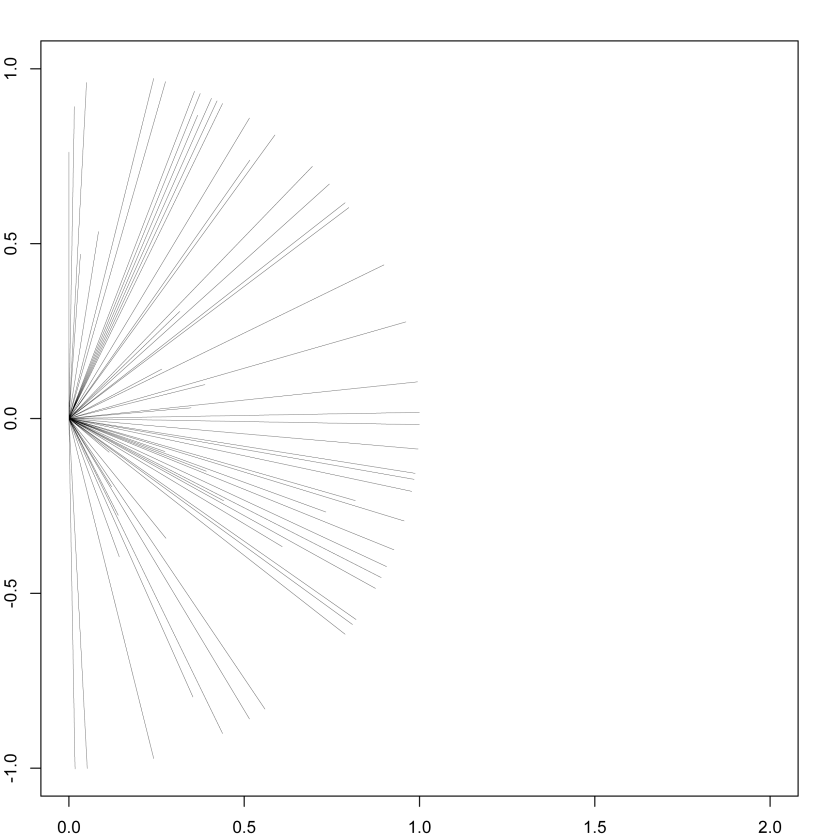

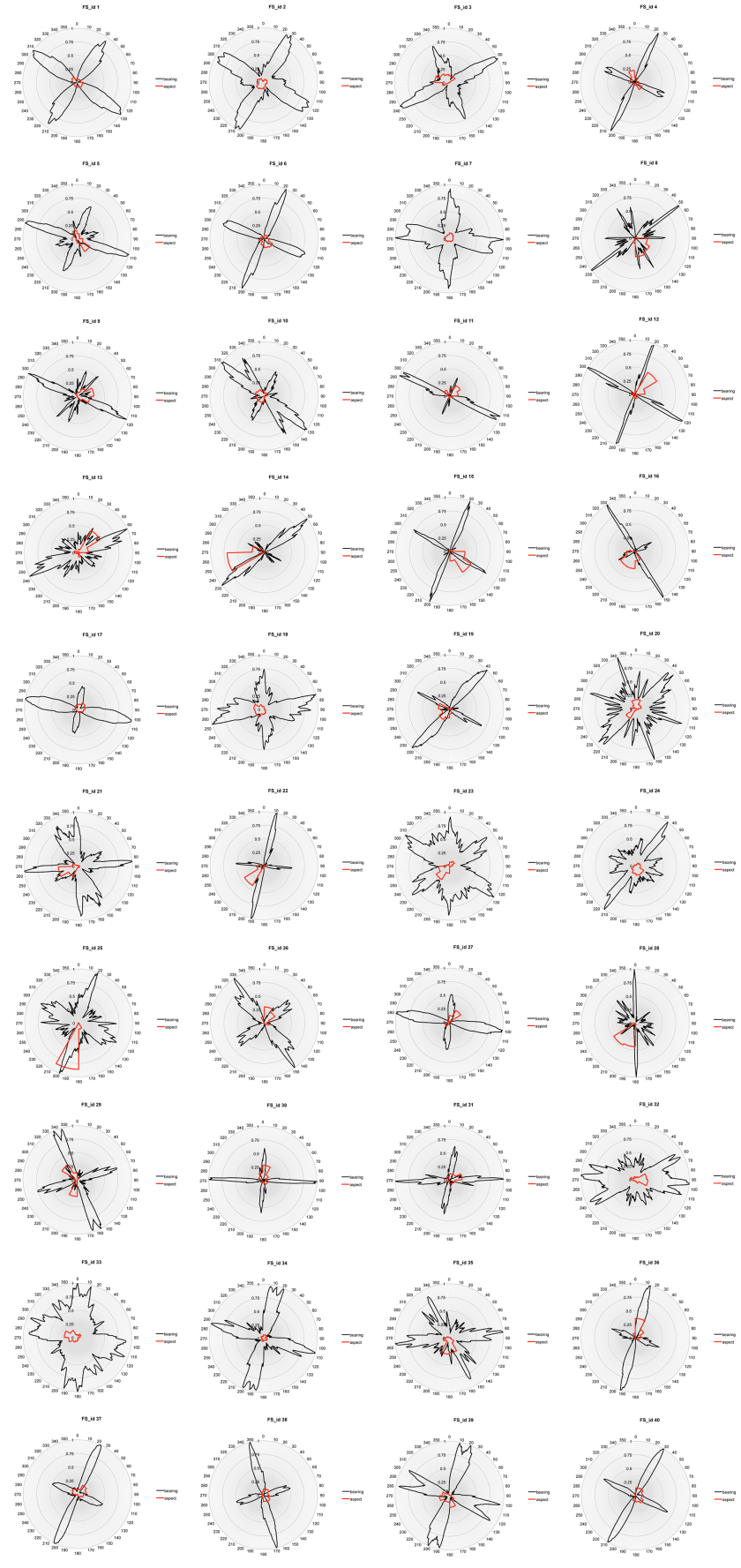

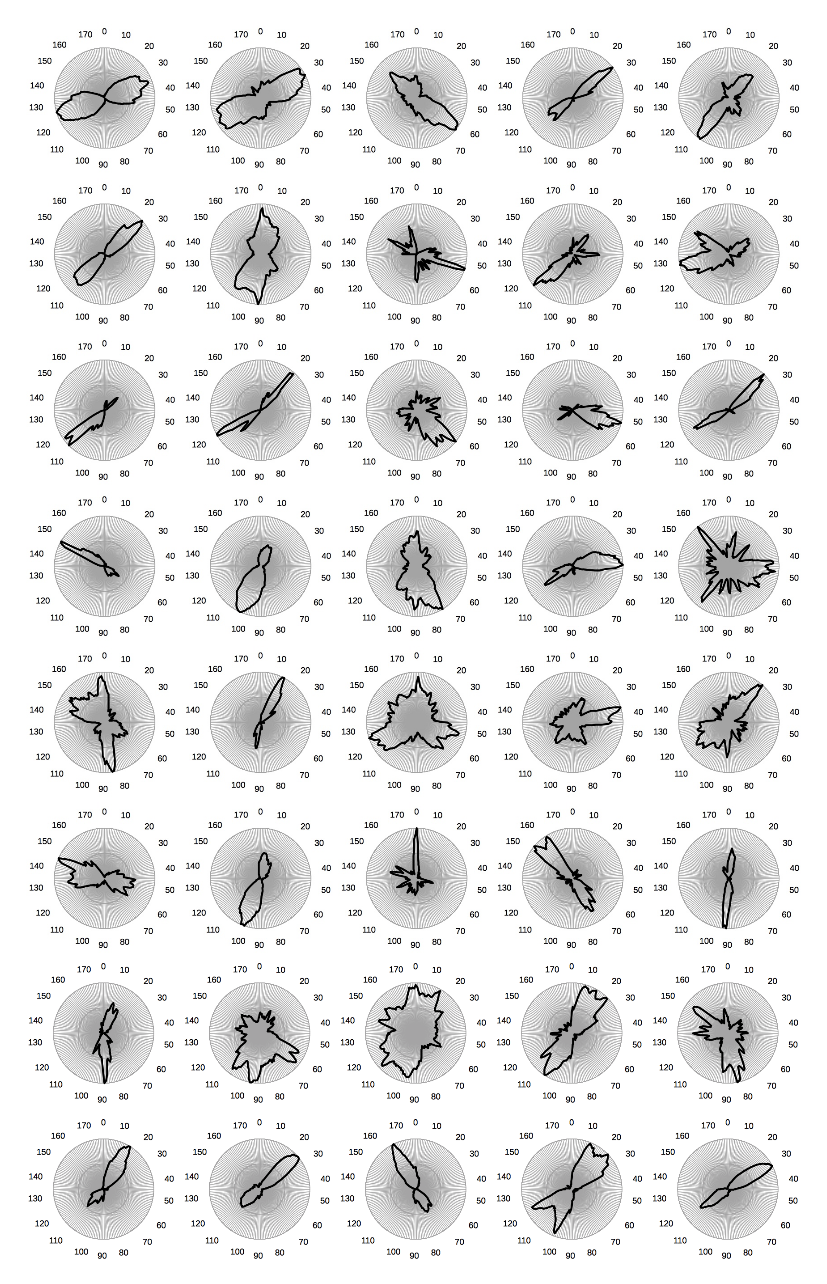

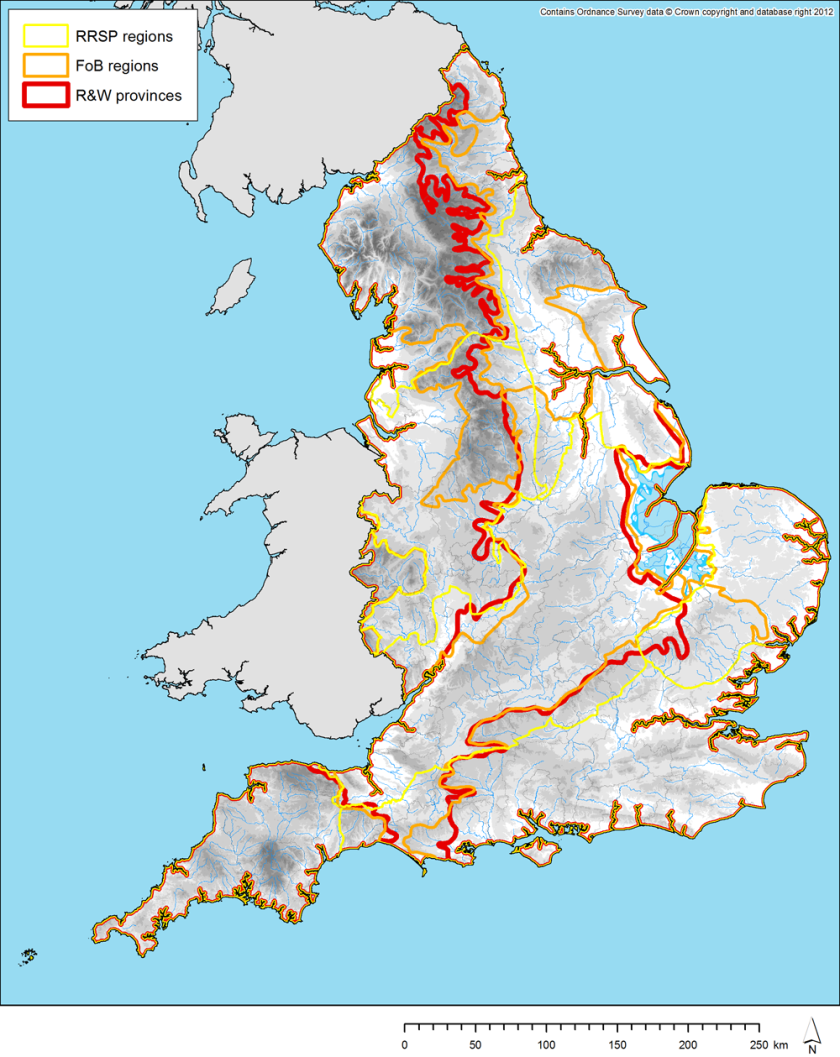

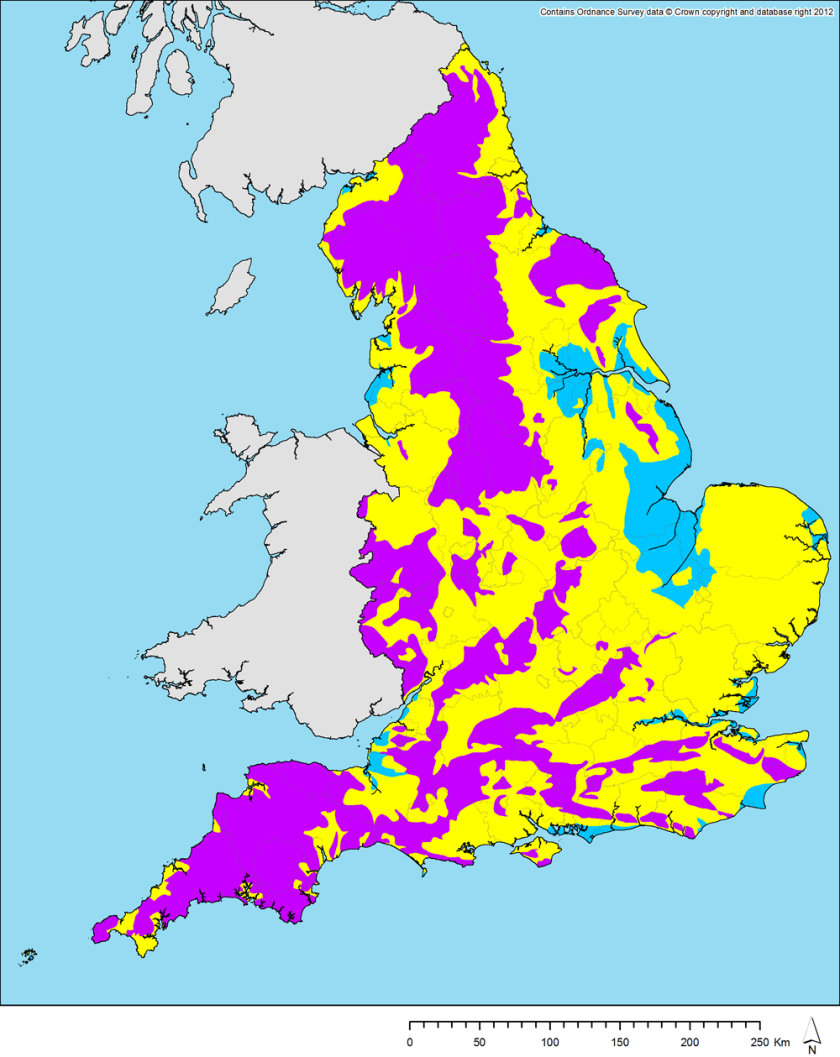

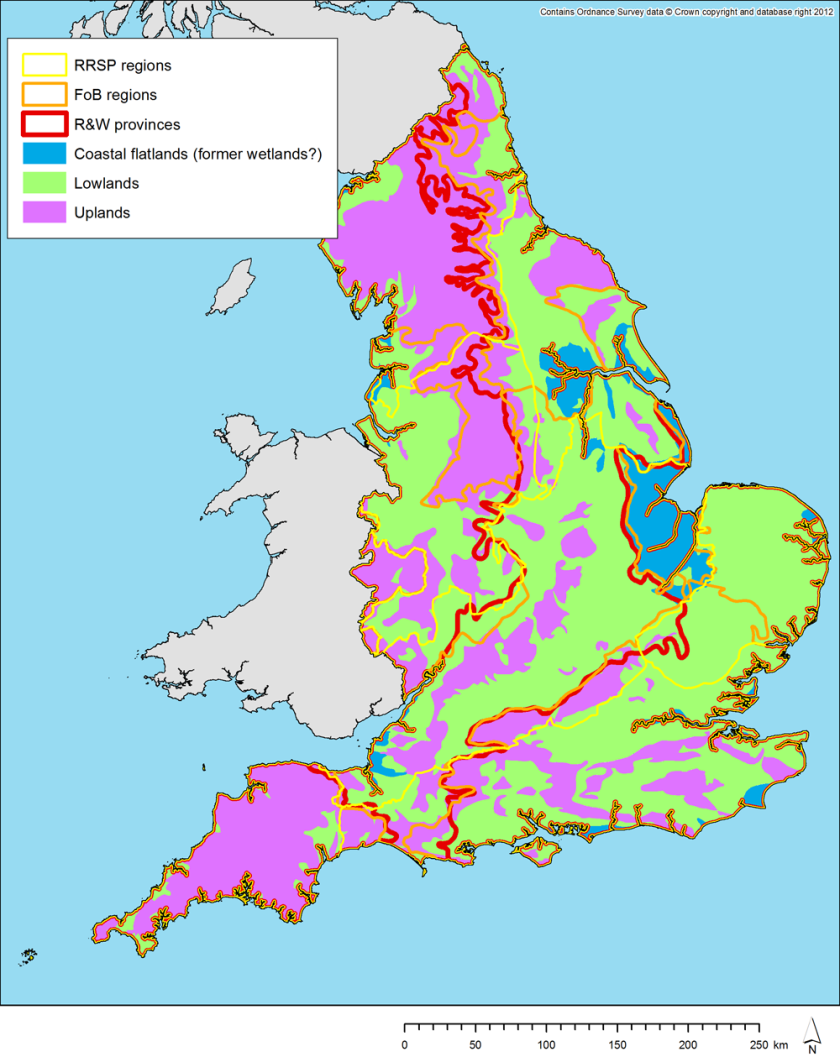

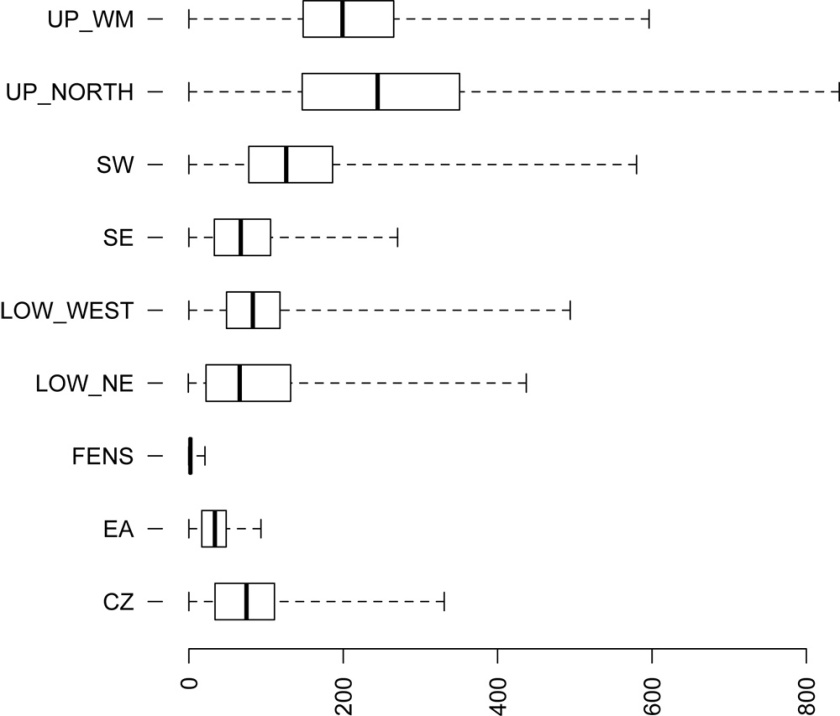

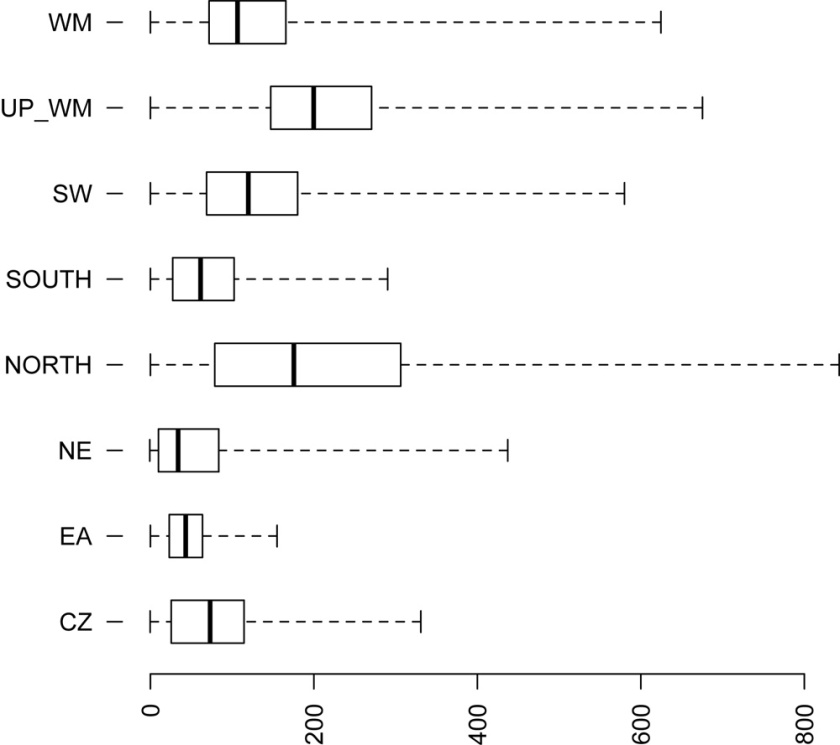

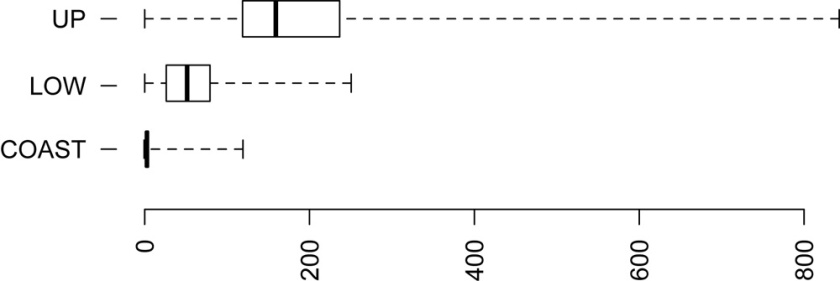

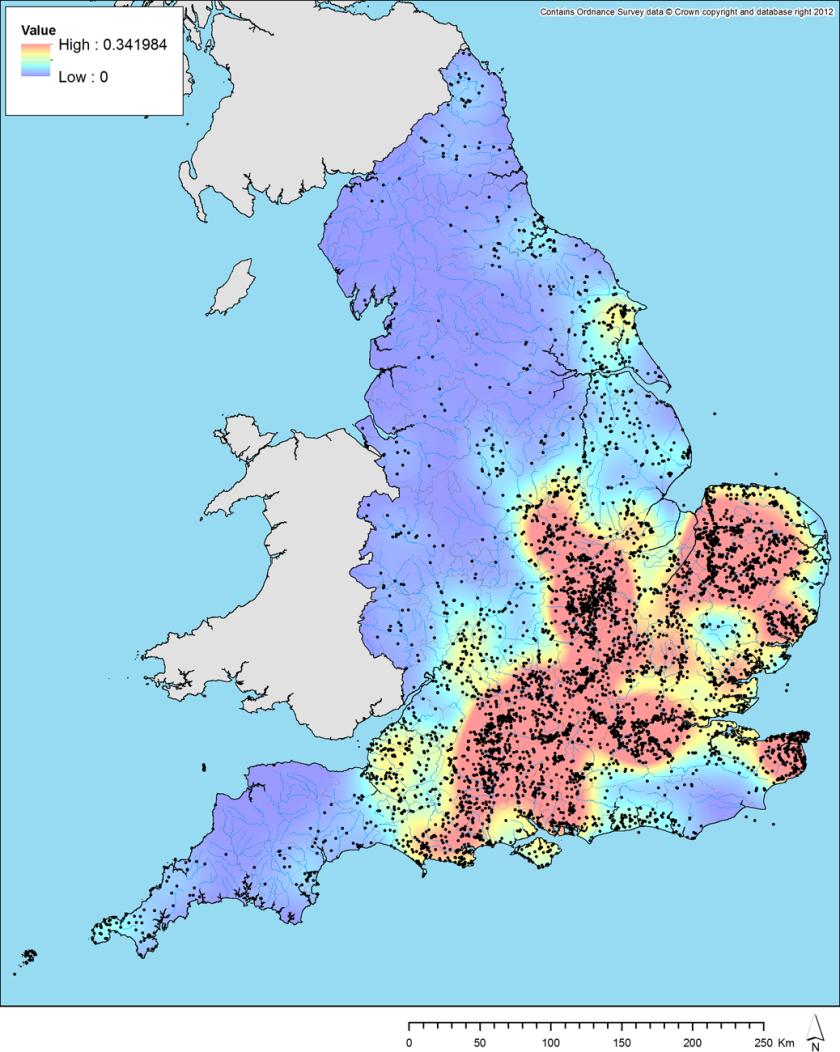

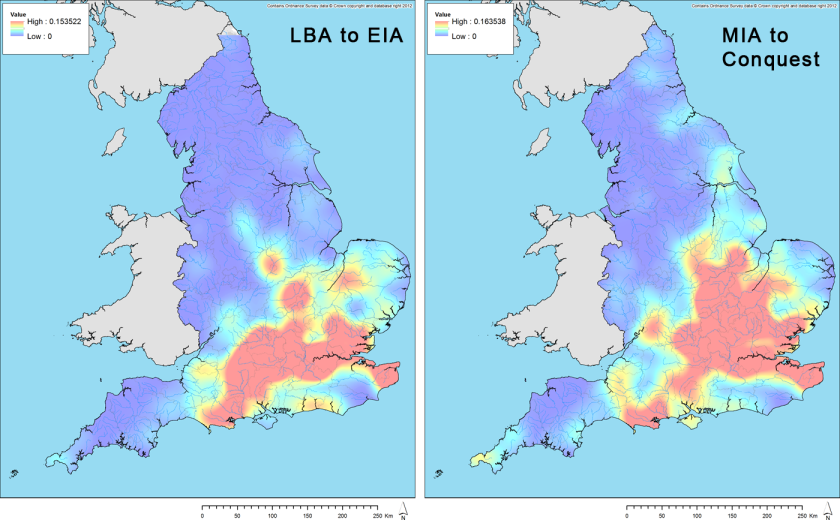

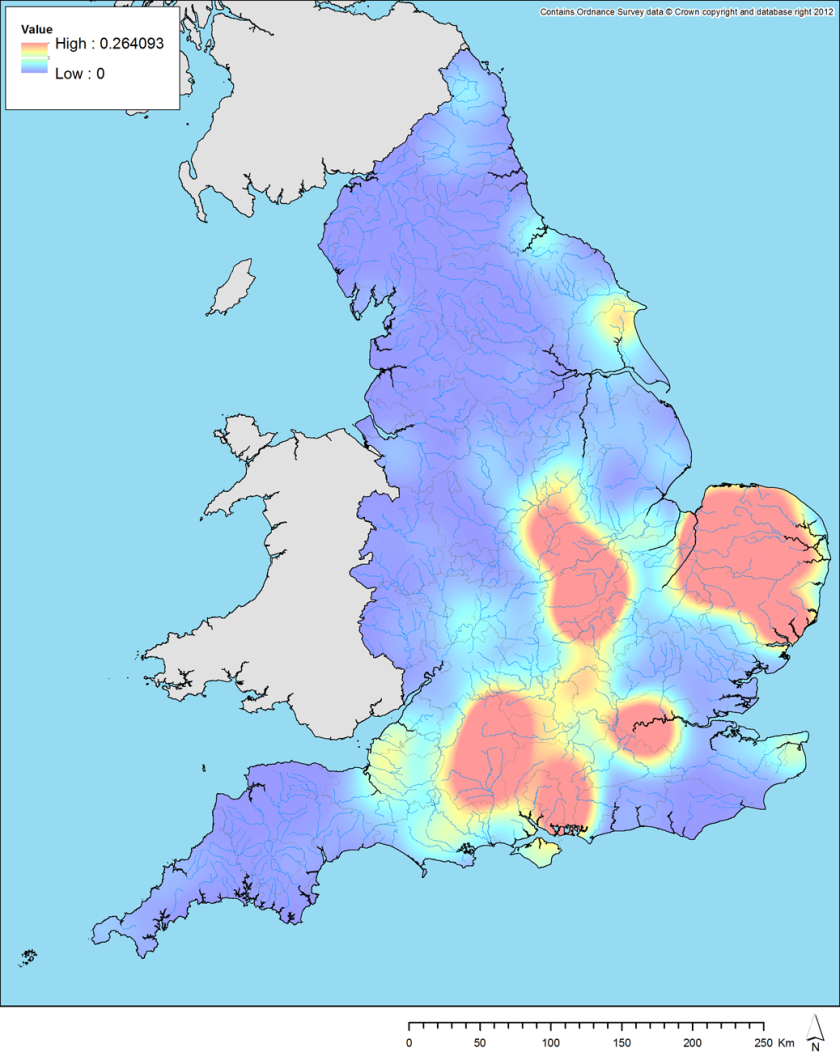

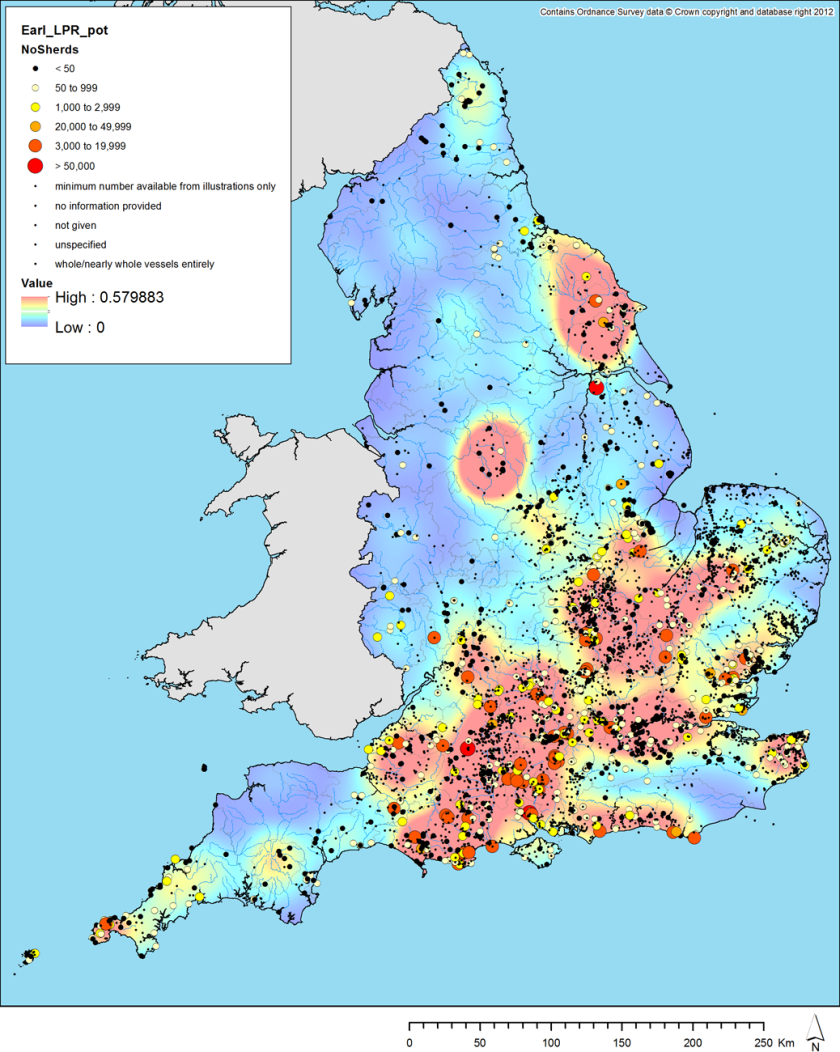

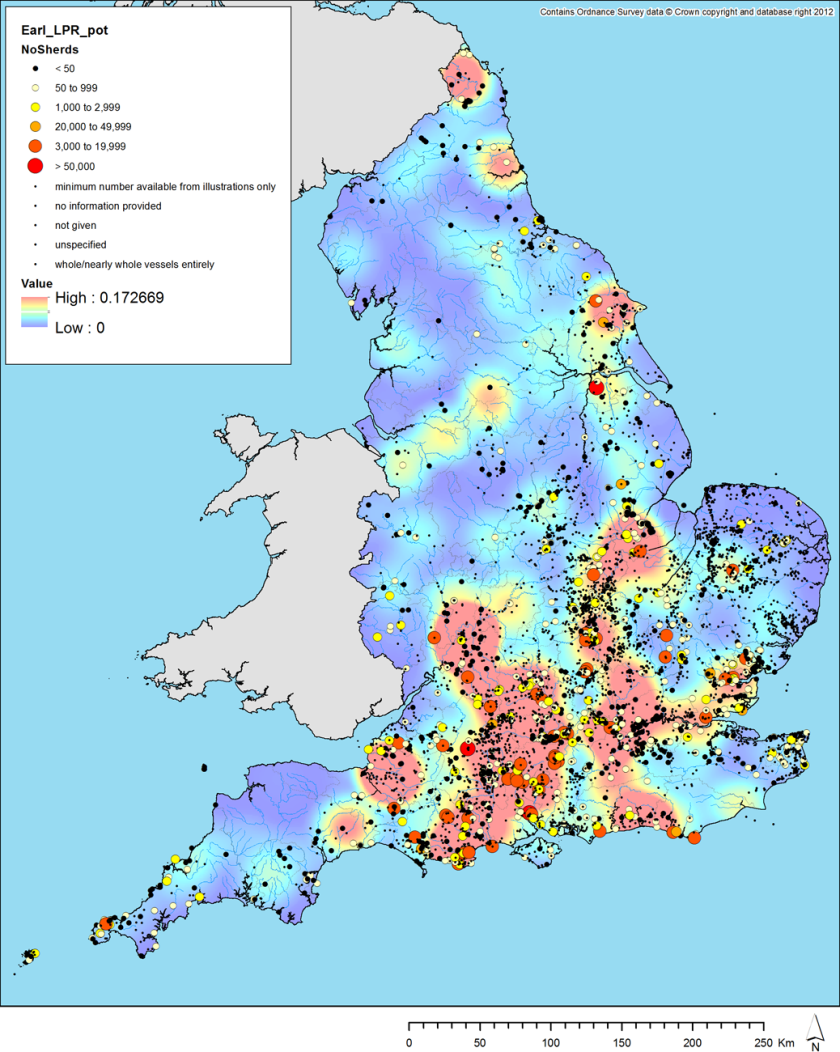

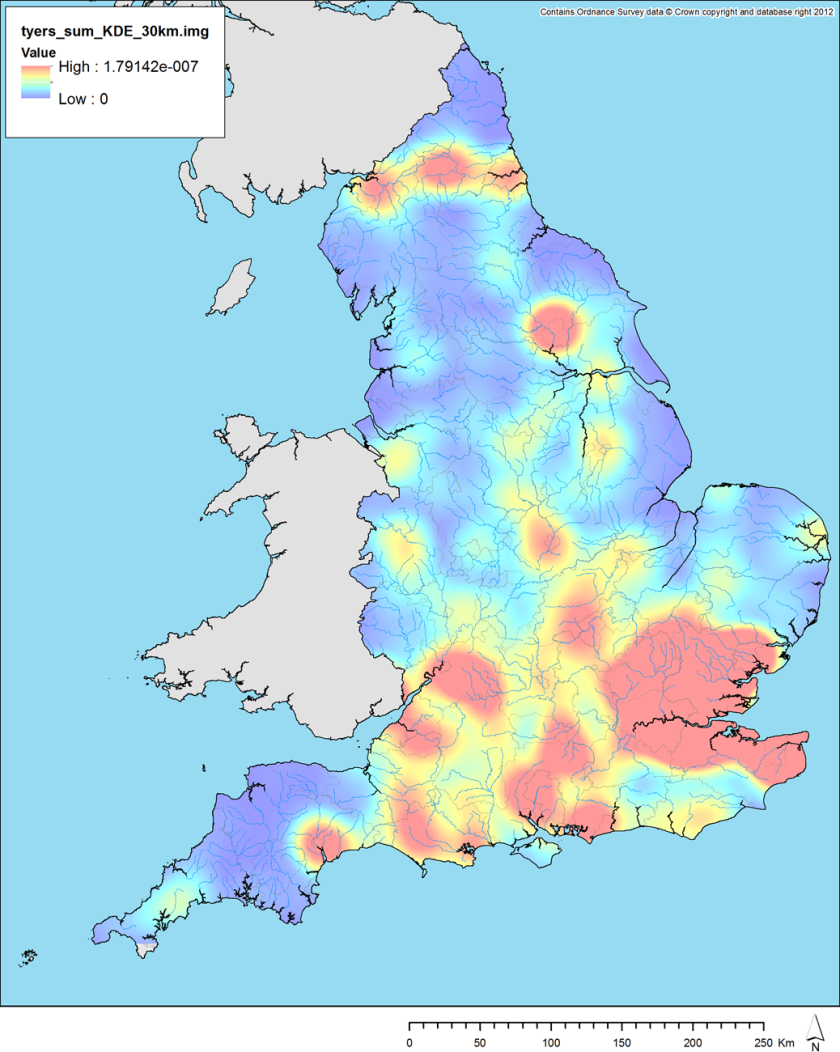

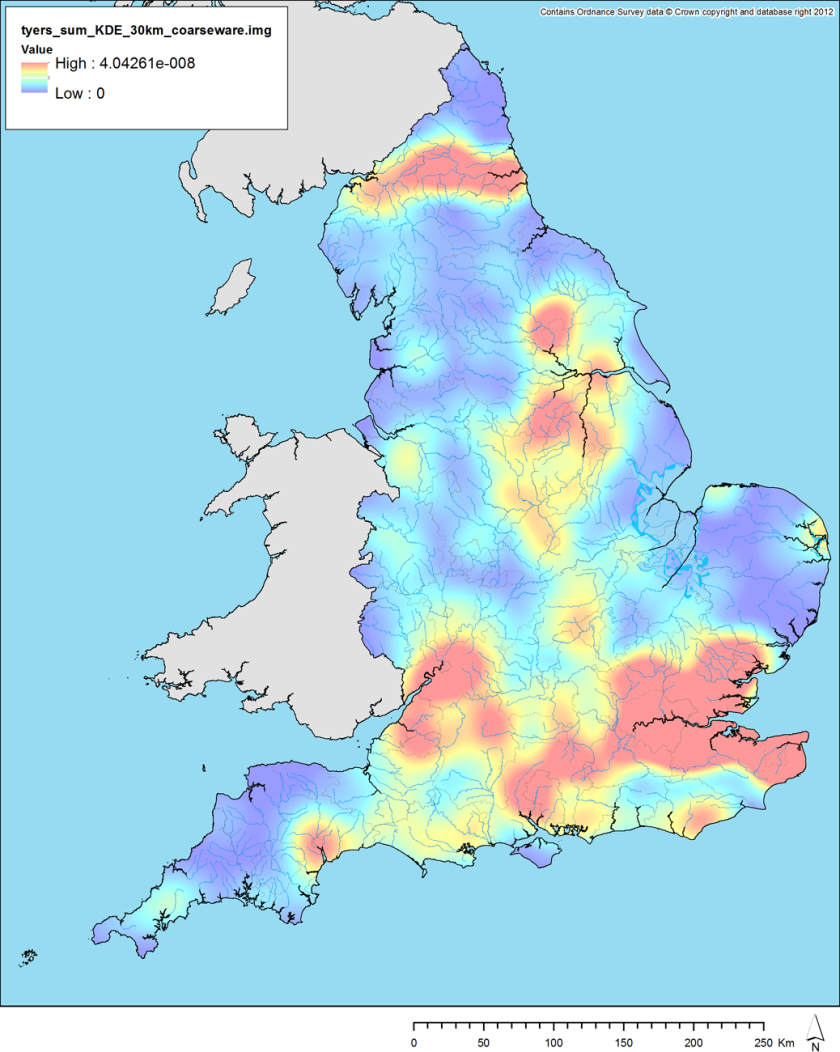

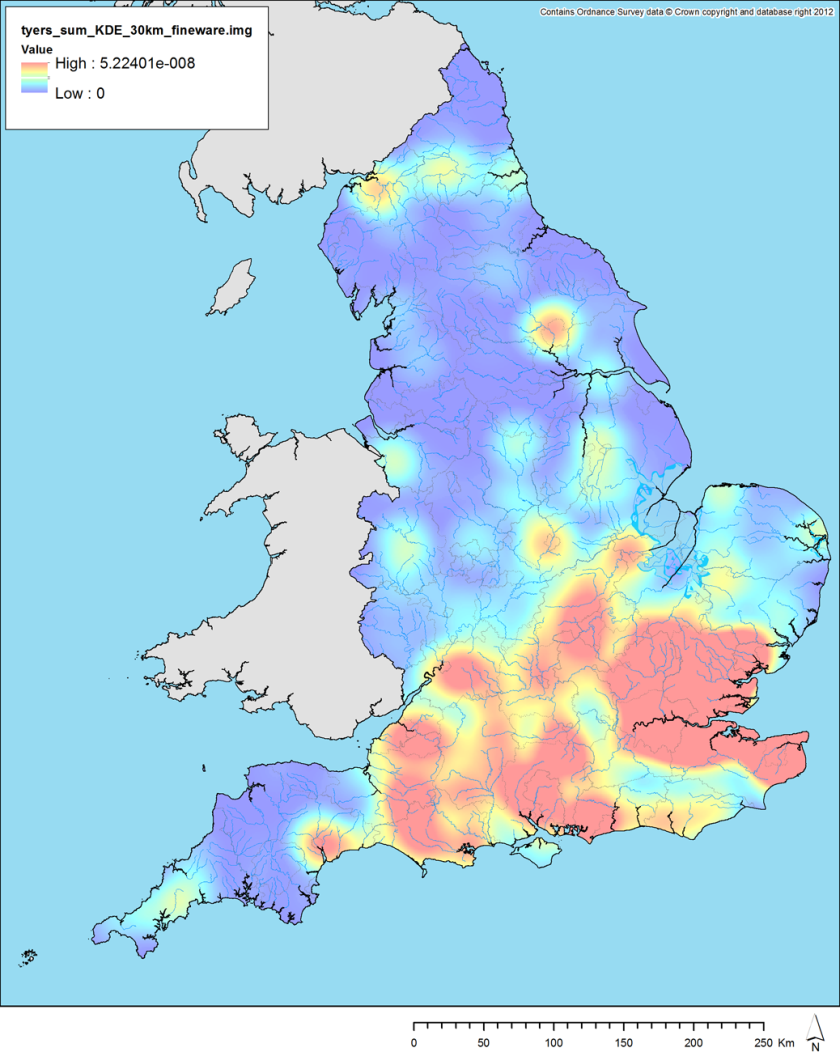

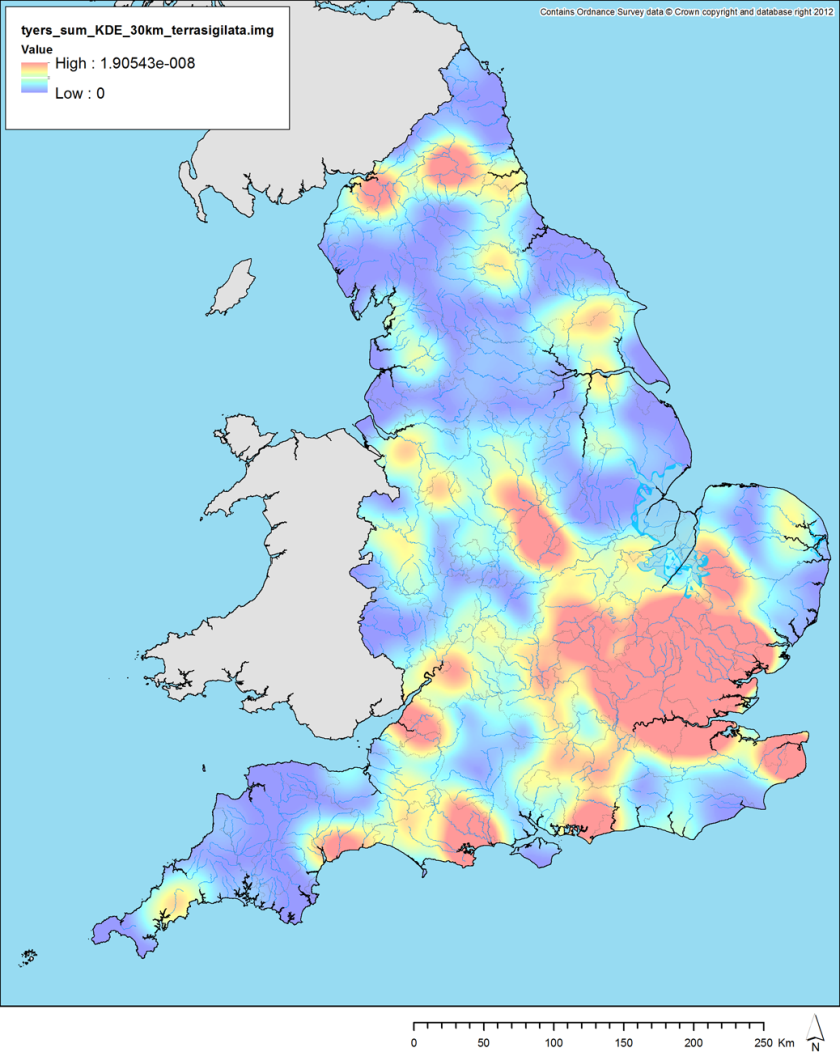

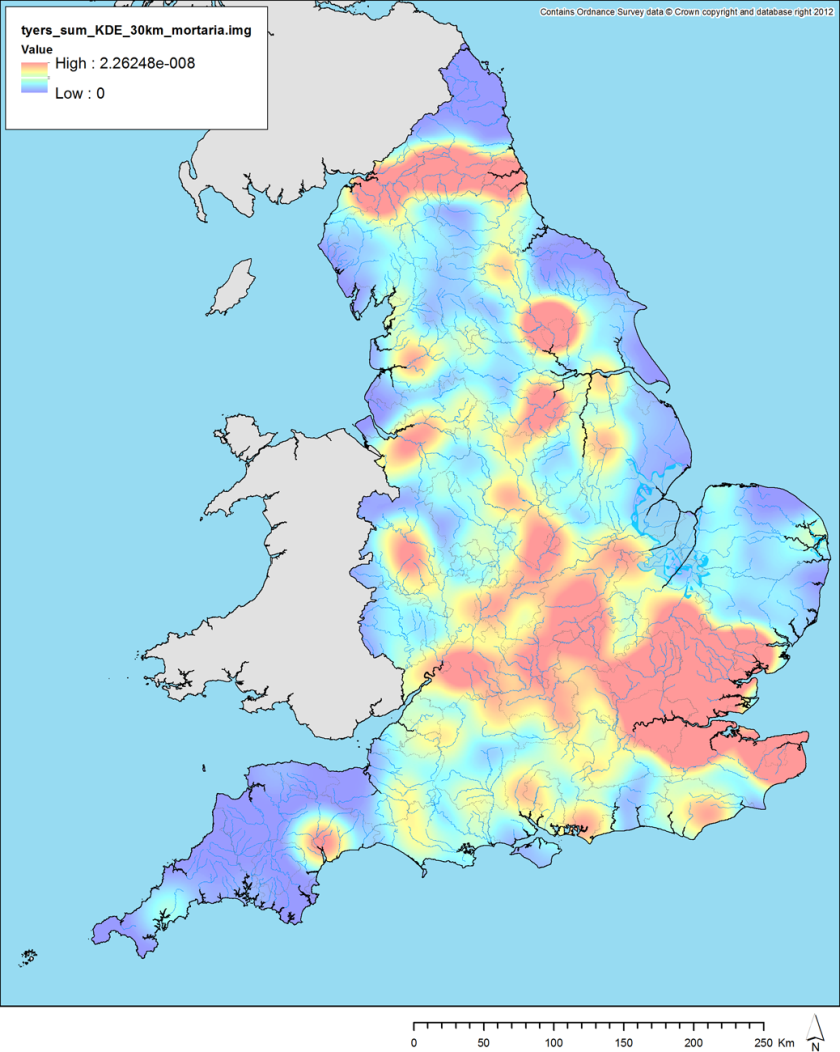

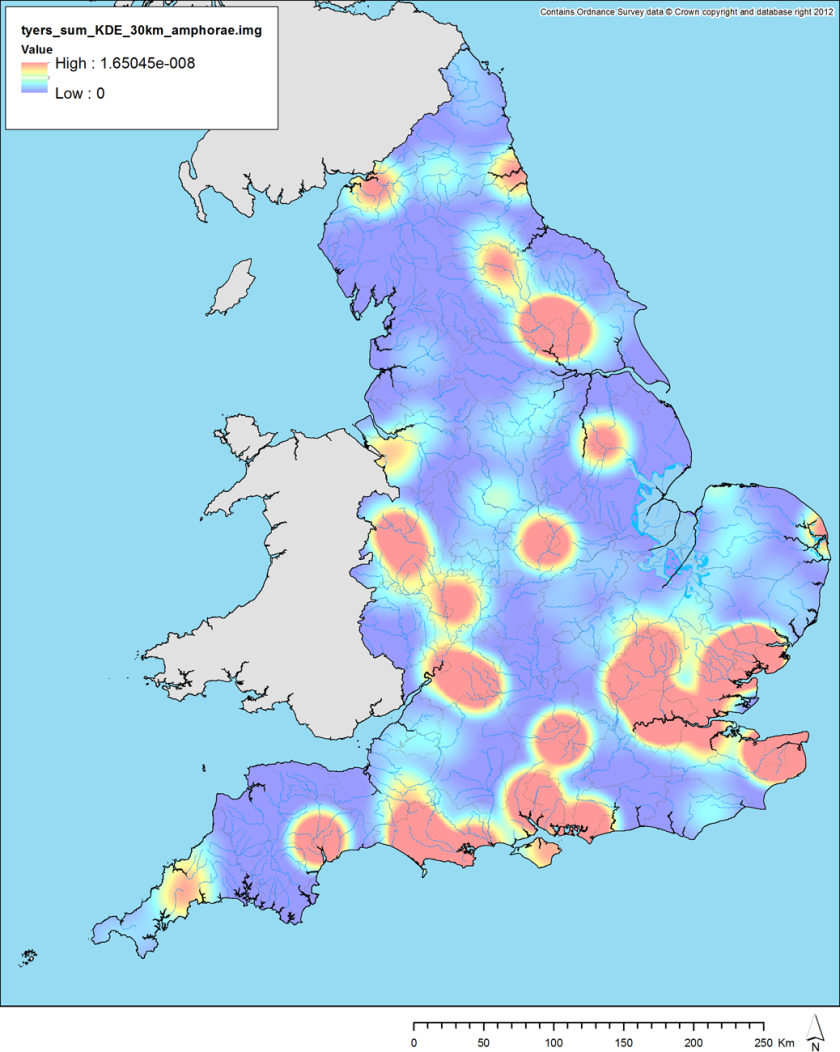

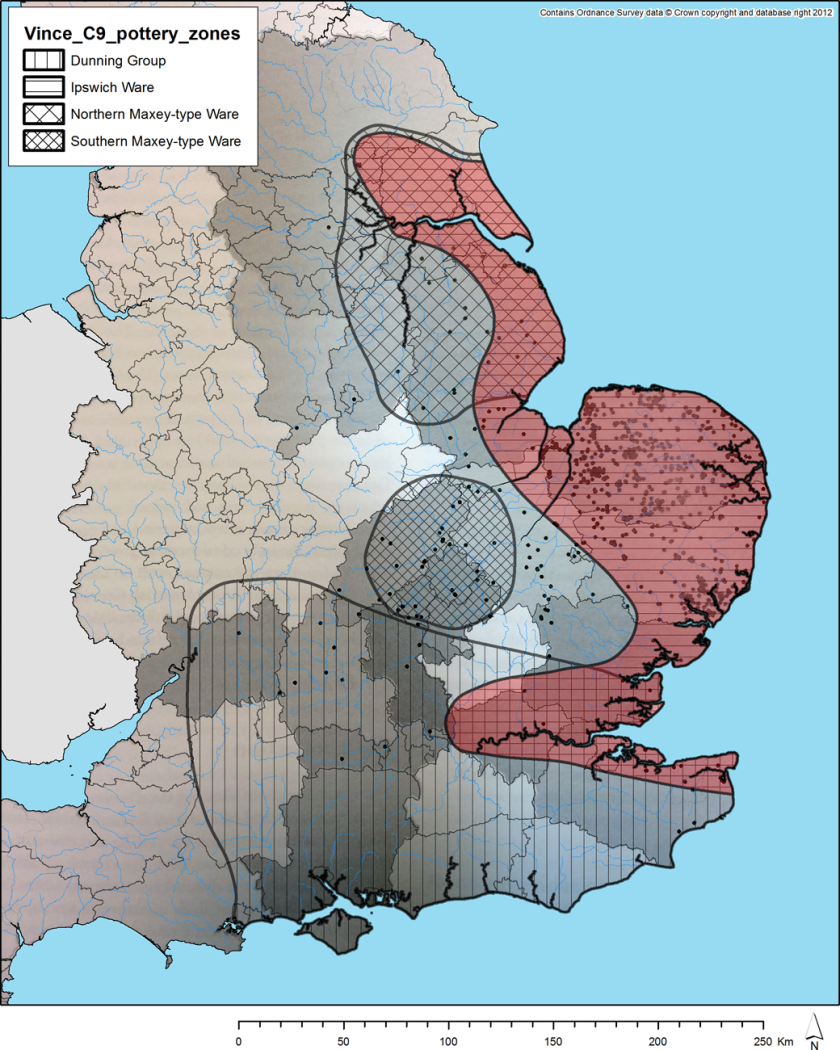

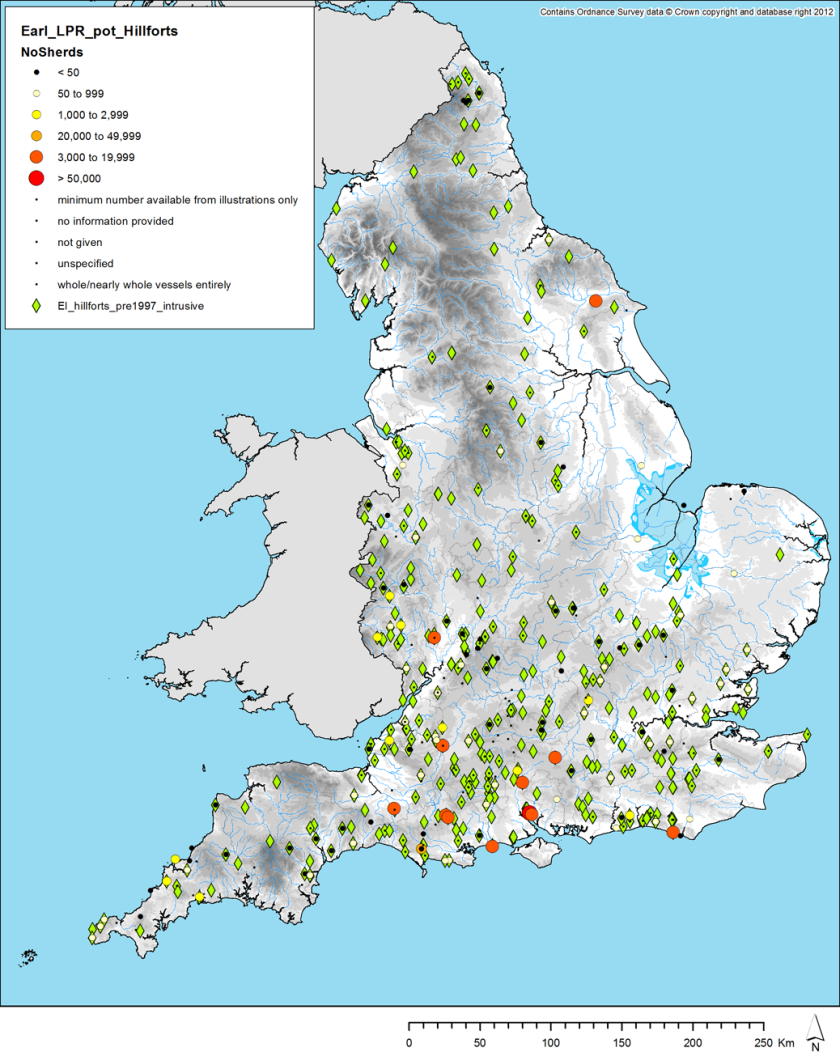

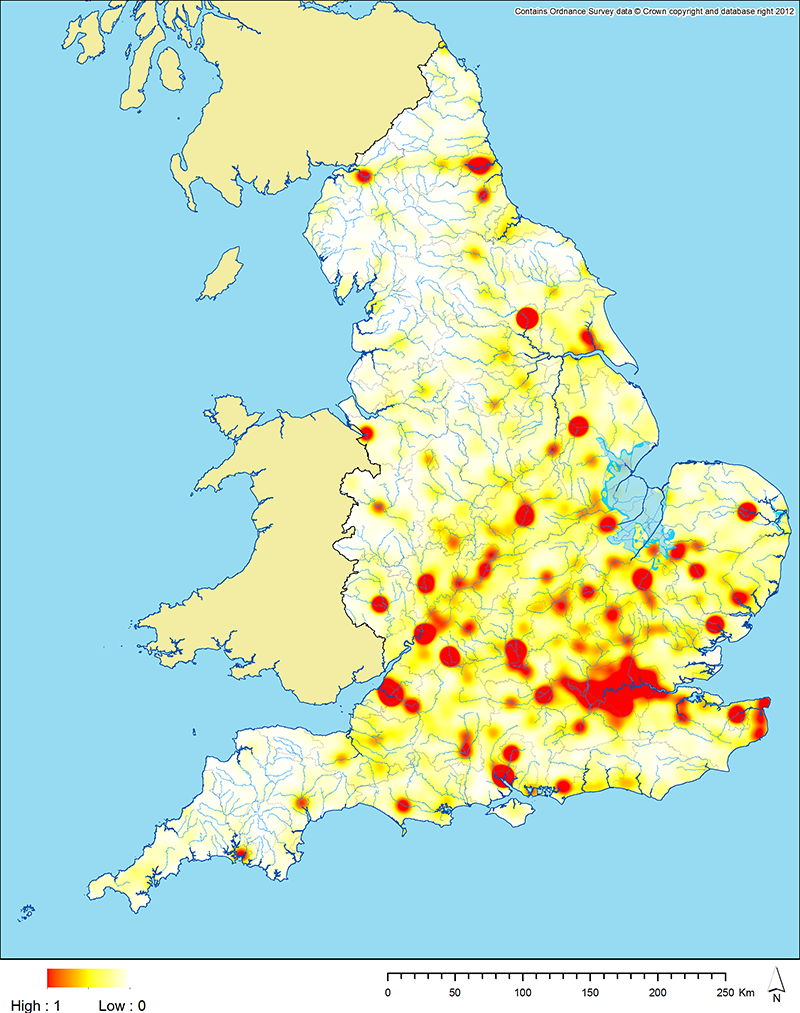

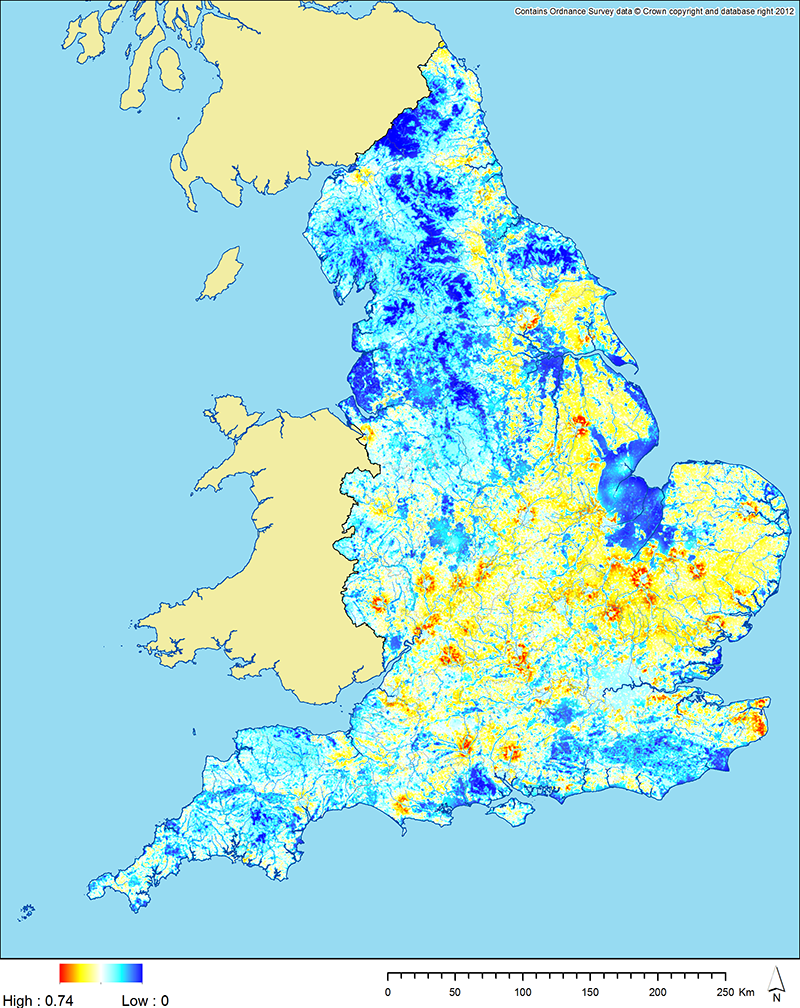

Spatial scale is one of the attributes of archaeological data that we can approach using map production methods inspired by the Uncertainty Principle. For spatial scale, its linked attribute is spatial resolution: the size of the objects used on a map to represent the archaeological data, whether they be dots or spatial bins (see Green 2013 for more discussion on the latter). When working at broad scales, dots placed on a map will often cover many square kilometres of space and, as such, spatial precision matters less. As one moves in to narrower spatial scales, spatial precision becomes more important and the spatial resolution of the objects should become finer. To give examples from within the context of EngLaId (Figure 13.5a–b), at our broadest spatial scales (all of England as a small printed image) the most appropriate forms for mapping distributions would be interpolated surfaces such as Kernel Density Estimates (KDE) (O’Sullivan & Unwin 2010: 68–71) or trend surfaces (O’Sullivan & Unwin 2010: 278–287), as these operate at coarse spatial resolutions where patterns remain visible that would be obscured or invisible if raw data was mapped (see Green et al. 2017). As our spatial scale narrows, we would move on to using various resolutions of aggregated spatial bins (Green 2013). Finally, at very narrow spatial scales, we would use the raw data directly exported from our database.

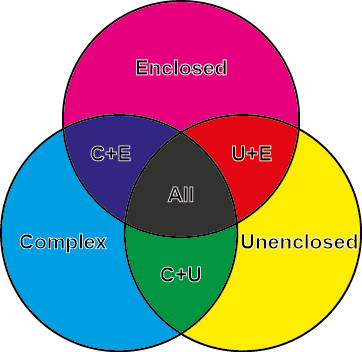

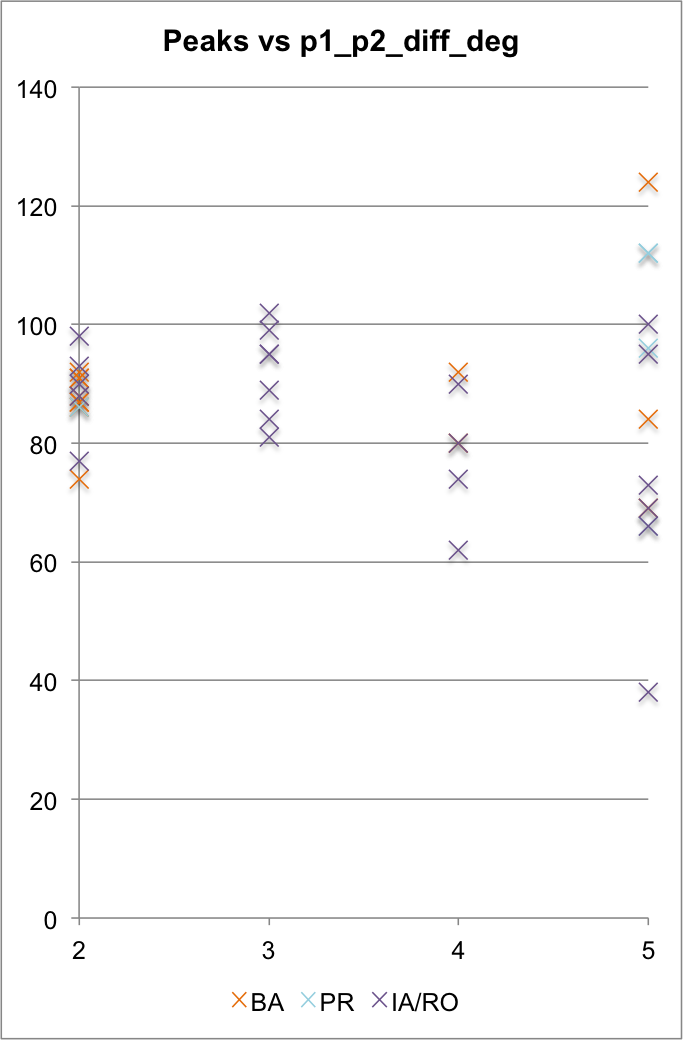

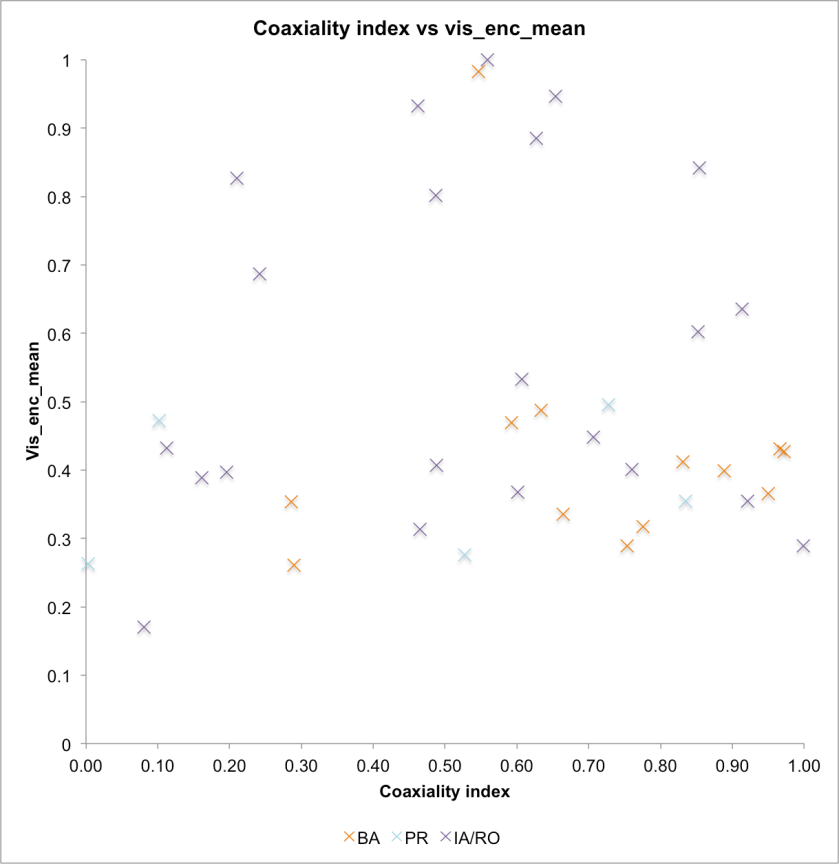

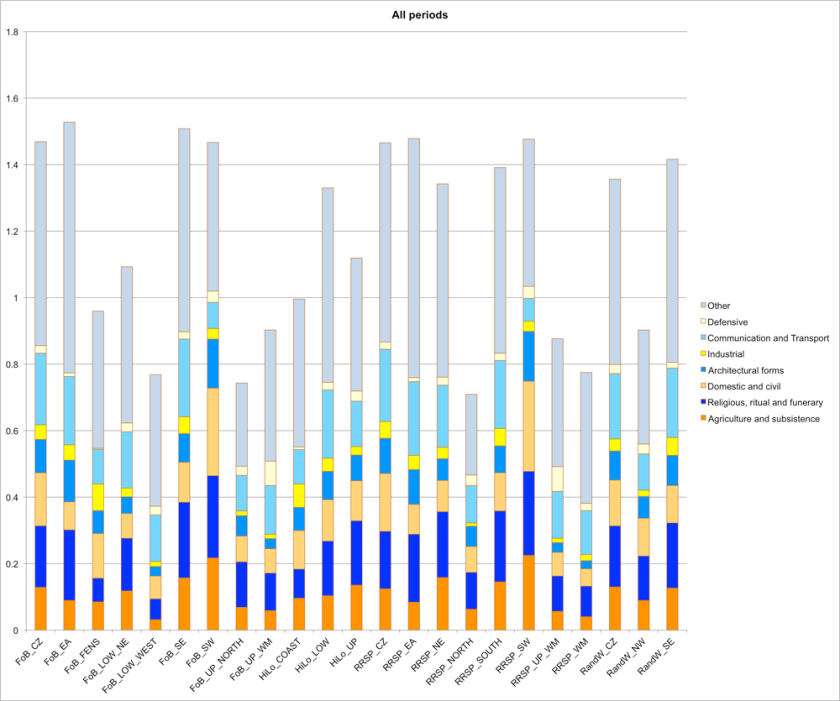

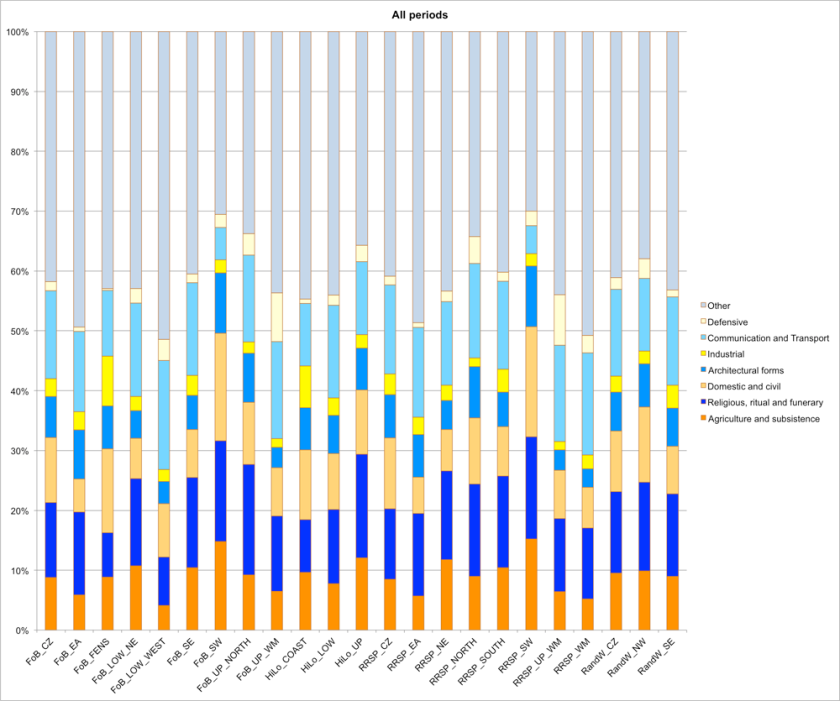

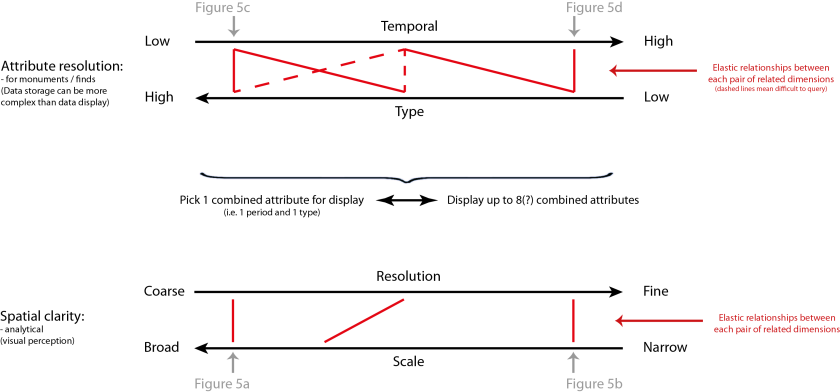

Fig. 13.5: Examples of maps from towards each extreme position; (a) broader scale, coarser resolution; (b) narrower scale, finer resolution; (c) coarser temporal precision, higher typological precision; (d) higher temporal precision, coarser typological precision.

The second set of linked attributes of archaeological data that can be conceptualised using the Uncertainty Principle as a metaphor are time and type. Time in archaeology can be represented at a range of precisions from the complex probabilities of scientific dates (e.g. probabilities output from software like OxCal; Bronk Ramsey 1994) through to very coarse broad time periods (e.g. Iron Age, Bronze Age, etc.). Equally, type of object (whether a site, an artefact, an ecofact, etc.) can be represented at a range of categorical precisions from the broad (e.g. defensive monument) through to the more specific (e.g. bivallate hillfort, or conceptually even a single specific site). Clearly, as a database representation, it is possible to store and manipulate all of this detail for every record in a dataset. However, to attempt to represent the full complexity of our objects cartographically would be impossible (or, at least, incomprehensible). As such, these two attributes can again be conceived as related within the bounds of the Uncertainty Principle: when making a map, the greater the temporal precision of mapped objects, the lesser the typological precision or complexity that should be applied. To give further examples from within the context of EngLaId (Figure 13.5c–d), if we were to map objects using precise temporal probabilities for time-slices, then only objects of a single type or of grouped types could be plotted on a map. Conversely, if we wished to create a map which showed the full gamut of site types in our database, then we could only map objects of a single time period (or all time periods grouped together). The latter case would still produce a map that was too complex to be understood by a reader, but the point is conceptually sound.

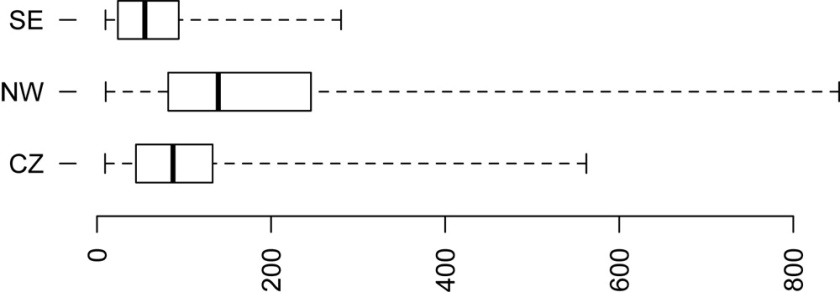

Bringing this all together (Figure 13.6), the two sets of related properties are also subject to a similar precision dependency. Broad spatial scale, coarse spatial resolution maps can only articulate relatively simple time / type relationships. Conversely, when working at narrower spatial scales and finer spatial resolutions, then more subtle time / type relationships can be more easily expressed. When working with this model in practice, an archaeological cartographer should begin by considering the research question which their proposed map is attempting to explore and who their anticipated audience is. Audience is key, as the complexity of a map can be at its greatest for internal analytical usage (as we can assume a researcher will be very familiar with their own data) and its lowest for public-facing usage (where we can assume no familiarity).

Fig. 13.6: Model depicting the application of the Uncertainty Principle to archaeological cartography.

Assuming a large dataset, if the research question requires very precise time and type, then it can only be answered at relatively narrow spatial scales and, as such, the researcher should start at the top of the model (in Figure 13.6) and work down. Conversely, if the research question requires working at broad spatial scales, then the researcher should start at the bottom of the model and work upwards. As a brief example, if one wished to make a five by five centimetre map of grave goods dating to between AD 50 and AD 100 in England, the resulting map would be best done as a density surface (due to the small image size) and could only feature the broad category of all grave goods, or alternatively one specific sub-category. In this way, when making a map of archaeological data, even an inexperienced cartographer ought to be able to ascertain a sense of what level of time / type complexity and what spatial scale / resolution they should be working at, through their metaphorical understanding of the Uncertainty Principle.

Providing Better Context for Distribution Mapping

As something of an aside and to move away from quantum theory, another key element of increasing the reputation of distribution mapping in archaeological circles lies in improving the contextual information provided to our maps’ audiences. It may be a cliché, but context is key to archaeological research, both on site and when zooming out to study broader areas of space. When mapping archaeological data regionally or nationally, it is important for cartographers to take account of the manner in which archaeological distributions are governed by patterns in fieldwork undertaken (Evans 2000: 3). This has become particularly important since the advent of developer funding of commercial archaeological fieldwork (in 1990 in Britain), as the location where the vast majority of investigations that take place since that time has been governed primarily by planning concerns rather than by archaeological research questions. This need not be conceived of as a problem to be corrected, but rather an element of the character of the data that should be studied and embraced (Cooper & Green 2016).

As such, it may be better to conceive of this relationship between fieldwork patterns and archaeological distributions using the concept of affordance. Introduced into archaeology via Ingold (1992), affordances are used within the discipline as a way of understanding the mutually constitutive relationship between people and their environment (Gillings 2007: 38–39). Essentially, the relationship between the archaeological record and patterns of development / fieldwork can be viewed in similar vein: practices in the modern world give rise to opportunities to analyse archaeological remains. Acquiring an understanding of this relationship is vital to understanding archaeological distributions today.

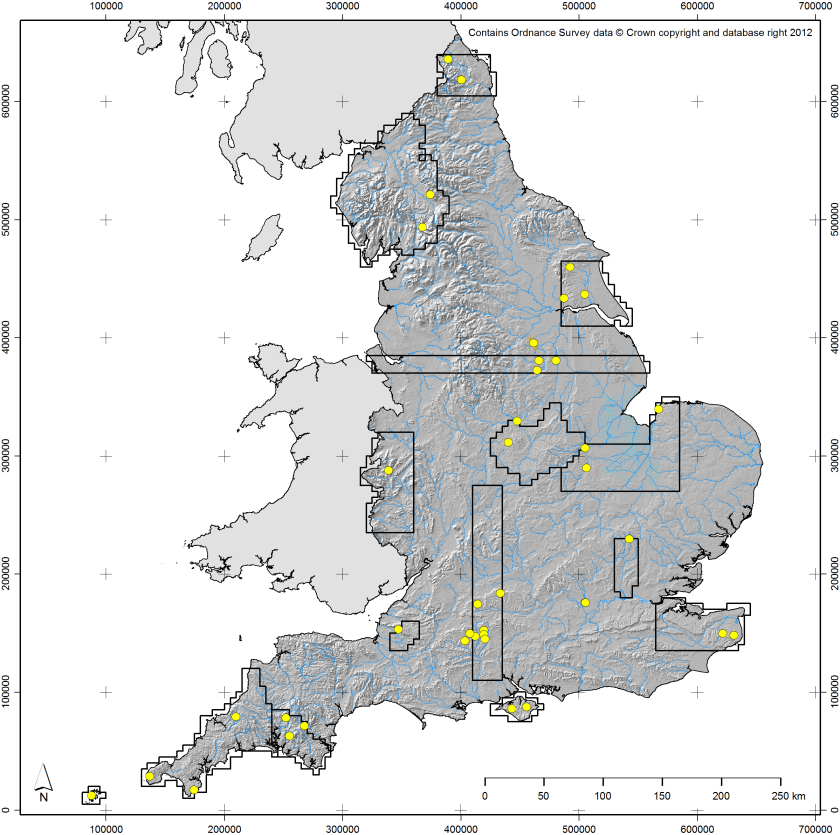

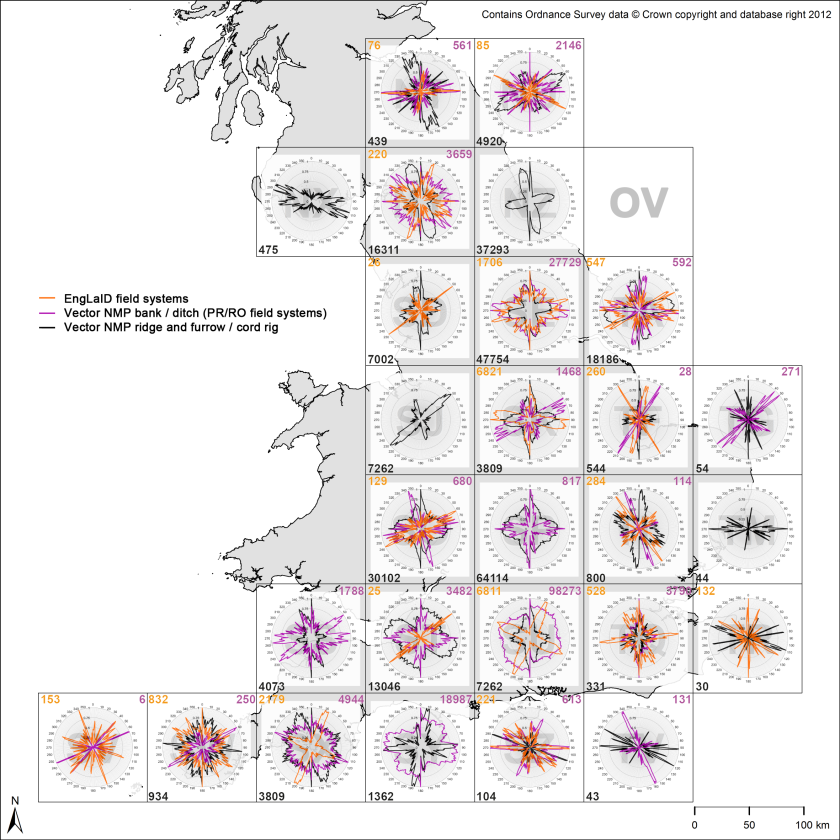

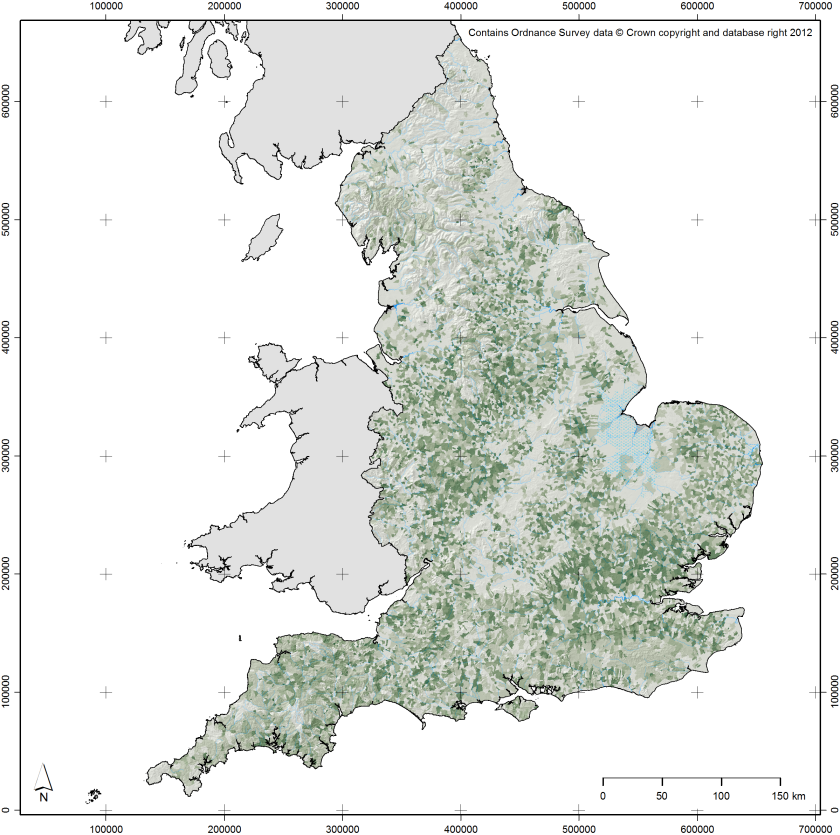

In order to enable quantitative analyses of this relationship, the EngLaId project constructed a model of modern affordances that have been affecting the structure of the archaeological record in England since 1990 (Figure 13.7) (for more on the structure of this model and the data built into it, see Green et al. 2017). This particular model reflects factors relating to excavation[4] and aerial photographic survey[5], currently the two most common sources for information that has entered the English archaeological record (LiDAR and geophysical survey are still only just starting to result in significant numbers of new “sites” in England, being mostly employed to study sites that were already known). We can use the model to test distributions of archaeological sites in an attempt to assess the extent to which they are influenced by modern fieldwork patterns or by more genuine patterns of past practice.[6] Contextualising our data in this way is vital if we wish to make our distribution mapping work better at communicating and explaining any patterns that we might discover, as the distributions we map are mostly no longer primarily structured by past practice (if they ever were). Modern affordances are just one example of better contextualisation, but they are a particularly key one. In combination with a more structured understanding (as discussed above) of the relationships between scale, resolution, time, and type, improving the contextual elements of archaeological maps can only make their messages more powerful.

Fig. 13.7: Model of modern affordances affecting the structure of archaeological distributions in England. This image contains modified data originally derived from: Historic England NRHE Excavation Index (hosted at: http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/304/); Centre for Ecology & Hydrology’s Land Cover Map 2007 (hosted at: http://doi.org/10.5285/2ab0b6d8-6558-46cf-9cf0-1e46b3587f13); NSRI National Soil Map of England and Wales (hosted at: http://www.landis.org.uk/data/natmap.cfm).

[4] Planning data was impossible to collate, so excavation affordances were modeled using the density of previous excavations from 1990 to 2010, including excavations with negative results and those that found material of any time period (to minimize bias introduced by focusing on specific periods).

[5] Factors affecting aerial photographic survey were modern land use (arable representing crop mark potential; pasture representing earthwork or parch mark potential) and obscuration of the ground surface, whether by above ground structures / water bodies / woodland or below ground masking superficial geologies / soil types.

[6] For example, hillforts score low on this model, as they tend to be in areas where opportunities to find archaeological material are low but being large and obvious monuments they tend to be easy to discover despite that. A monument category like Anglo-Saxon sunken featured buildings (also known as Grubenhäuser) score much more highly on the model, as they are less obvious and thus require greater levels of opportunity to be discovered.

Conclusions: Making Better Archaeological Maps?

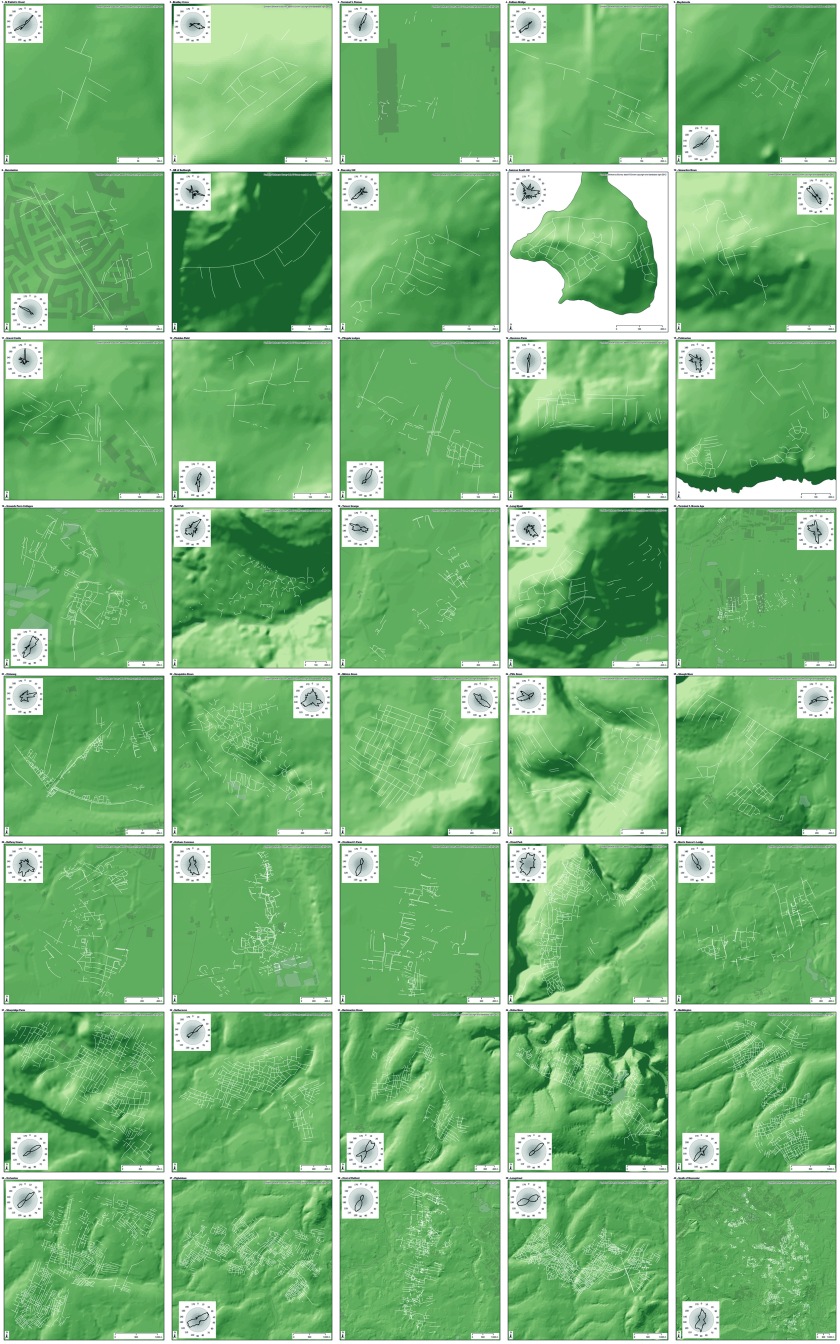

To return one final time to my autobiographical examples, since 2011 I have been employed on the EngLaId project as a postdoctoral researcher in GIS. As a result, I have spent many hours making many different maps of many different datasets. I have regularly made maps for my own purposes, for other project members, and for other people working within our department. As a result, my skills as a cartographer have improved immensely, to the extent that I often feel quite a strong sense of pride over the maps that I produce (e.g. Figure 13.8). Distilling that experience into a model of good cartographic practice for my own purposes and for the help of others has resulted in this paper.

Fig. 13.8: Map created by the author in 2016. Darker green shading depicts greater levels of woodland cover in the eleventh century AD (after Roberts & Wrathmell 2000: figure 24), collated by post-medieval parishes (Burton et al. 2002). This image contains data derived from Sturt et al. 2013 (the former sea levels around The Wash).

Generally speaking, in my work I start with the question of scale and move upwards through the model outlined above, considering resolution next to maximise the legibility of the map produced. For example, although there are statistical methods for determining the appropriate kernel size for a KDE surface (e.g. the Mean Integrated Squared Error; Marron & Wand 1992), making a choice based upon cartographic legibility seems more logical to me as that should always be a key concern when making any map. Visualization for the purposes of research (of which map making is but one strand amongst many) exists to save time during the processes of discovery and communication of information and knowledge (Chen et al. 2014), with “pleasantness” key to visual efficiency (Kent 2005: 184). As a specific technique, map design lies at the central point between art, science, and technology, with no single recipe for success (Field & Demaj 2012: 73–75). As such, cartographic concerns such as legibility (including taking account of colour blind audience members) and aesthetic appeal should be foremost in our minds when making maps. A metaphorical understanding of the Uncertainty Principle as outlined above can aid greatly in that task, providing guidance to aid the archaeological cartographer without dictating or attempting to control methods or outputs.

We make maps and use GIS in an attempt to make sense of the geographical world: they are as artistic and as political (Crampton 2010: 3, 12) as the world around us. They imperfectly reflect (or refract?) reality and should be embraced as such. Thus, we should not be anxious about cartography in and of itself, only anxious about approaching it uncritically (Crampton 2010: 184). Maps are no longer only useful for the increasingly moribund hypothesis testing / pattern confirmation practices of the old scientific method, but can be vital to modern exploratory data analysis / pattern seeking methodologies (Crampton & Krygier 2006: 24) as part of hybrid approaches to understanding the world / archaeology (Hacıgüzeller 2012: 257) through suggestion, not definition, of spatial patterning (Sturt 2006: 131).

Distribution mapping of archaeological material remains vital to the understanding and communication of the results of fieldwork and other investigations, giving a flavour of space and presenting an idea of the relationship between archaeological remains and local / regional topography (Sturt 2006: 131). Careful cartographic choices (e.g. using models such as that outlined above) and an understanding of context (including modern affordance patterns) are vital for achieving critical comprehension of our material in all of its wonderful character. Archaeologists are very rarely trained cartographers, but this should not be seen as a problem, more as an opportunity. Hopefully, the ideas outlined in this chapter will help guide those wishing to make maps of archaeological data down fruitful avenues, whereby effective communication is enabled through an understanding of the vital inherent relationships between scale / resolution and time / type. Finally, I will leave it up the reader to decide if I have improved as a cartographer since I made my first maps in the late 1990s, but I am certain that my creation of the model presented here has aided in whatever improvement I have achieved.

Acknowledgements

This paper was written whilst working on the English Landscapes and Identities Project (EngLaId) at the University of Oxford. EngLaId has been funded by the European Research Council (Grant Number 269797). My thanks go to the other members of the EngLaId team for providing a stimulating research environment without which this work would not have come to fruition. In particular, the ideas presented in this paper arose out of fruitful discussions with Anwen Cooper on the capacities of our evidence and how we can present it to the world. I would also thank Anwen Cooper, Miranda Creswell, Victoria Donnelly, Michaela Ecker, Letty ten Harkel, and Sarah Mallet for helpful feedback on draft versions of this paper, as well as the editors of this volume for the further useful advice.

Bibliography

Bronk Ramsey, C. (1994). Analysis of chronological information and radiocarbon calibration: the program OxCal. Archaeological Computing Newsletter, 41, 11–16.

Burton, N., Westwood, J., & Carter, P. (2002). GIS of the Ancient Parishes of England and Wales, 1500–1850 [dataset]. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor]. SN: 4828.

Chen, M., Floridi, L., & Borgo, R. (2014). What is visualization really for? The Philosophy of Information Quality. Springer Synthese Library Volume 358, 75–93.

Collins, K. (2013). Uncharted territory: amateur cartographers fight to put their communities on the map. Wired. http://www.wired.co.uk/article/slum-mapping-google-maps-cartography. Accessed 31 January 2017.

Cooper, A., & Green, C. (2016). Embracing the complexities of ‘Big Data’ in archaeology: the case of the English Landscape and Identities Project. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 23, 271–304.

Crampton, J.W. (2010). Mapping. A Critical Introduction to Cartography and GIS. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Crampton, J.W., & Krygier, J. (2006). An introduction to critical cartography. ACME: an International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 4(1), 11–33.

Dent, B., Torguson, J.S., & Hodler, T.W. (2009). Cartography: Thematic Map Design. New York: McGraw Hill.

Evans, C. (2000). Archaeological distributions: the problem of dots. In Kirby, T. and S. Oosthuizen (Eds.) An Atlas of Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire History. Cambridge: Centre for Regional Studies, Anglia Polytechnic University, 3–4.

Field, K. (2005). Maps still matter – don’t they? Cartographic Journal 42(2), 81–82.

Field, K. (2009). Cartographic Twitterings. Cartographic Journal 46(2), 59–61.

Field, K. (2014). A cacophony of cartography. Cartographic Journal 51(1), 1–10.

Field, K. (2015). Re-freshing cartography. Cartographic Journal 52(2), 93–94.

Field, K., & Demaj, D. (2012). Reasserting design relevance in cartography: some concepts. Cartographic Journal 49(1), 70–76.

Gartner, G. (2009). Web mapping 2.0. In Dodge, M., R. Kitchin, & C. Perkins (Eds.) Rethinking Maps. London & New York: Routledge, 68–82.

Gillings, M. (2007). The Ecsegfalva landscape: affordance and inhabitation. In Whittle, A. (Ed.) The Early Neolithic on the Great Hungarian Plain. Investigations of the Körös Culture Site of Ecsegfalva 23, County Békés. Budapest: Publicationes Instituti Academiae Scientarium Hungaricae Budapestini, 31–46.

Green, C.T. (2011). Winding Dali’s Clock: the Construction of a Fuzzy Temporal-GIS for Archaeology. BAR International Series 2234. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Green, C. (2013). Archaeology in broad strokes: collating data for England from 1500 BC to AD 1086. In Chrysanthi, A., D. Wheatley, I. Romanowska, C. Papadopoulos, P. Murrieta-Flores, T. Sly, G. Earl (Eds.) Archaeology in the Digital Era: Papers from the 40th Annual Conference of Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology (CAA), Southampton, 26–29 March 2012. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 307–312.

Green, C., Gosden, C., Cooper, A., Franconi, T., Ten Harkel, L., Kamash, Z., & Lowerre, A. (2017). Understanding the spatial patterning of English archaeology: modelling mass data, 1500BC to AD1086. Archaeological Journal 174(1), 244–280 .

Hacıgüzeller, P. (2012). GIS, critique, representation and beyond. Journal of Social Archaeology 12(2), 245–263.

Hawking, S. (2011). A Brief History of Time: from the Big Bang to Black Holes. London: Bantam.

Heisenberg, W. (1927). Über den anschaulichen Inhalt der quantentheoretischen Kinematik und Mechanik. Zeitschrift für Physik 43(3–4), 172–198.

Ingold, T. (1992). Culture and the perception of the environment. In Croll, E. and D. Parkin (eds) Bush Base, Forest Farm: Culture, Environment, and Development. London: Routledge, 39–56.

Kent, A.J. (2005). Aesthetics: a lost cause in cartographic theory? Cartographic Journal 42(2), 182–188.

Lock, G., & Molyneaux, B.L. (Eds.) (2006a). Confronting Scale in Archaeology. Issues of Theory and Practice. New York: Springer.

Lock, G., & Molyneaux, B.L. (2006b). Introduction: confronting scale. In: Lock and Molyneaux 2006a, 1–11.

MacEachren, A.M. (1995). How Maps Work. Representation, Visualization, and Design. New York: Guildford Press.

Marron, J.S., & Wand, M.P. (1992). Exact Mean Integrated Squared Error. The Annals of Statistics 20(2), 712–736.

Monmonier, M. (1996). How to Lie With Maps. Second Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Olivier, L. (2001). Duration, memory and the nature of the archaeological record. In Karlsson, H. (Ed.) It’s about Time: The Concept of Time in Archaeology. Göteborg: Bricoleur Press, 61–70.

Olivier, L. (2011). The Dark Abyss of Time: Archaeology and Memory. Lanham: AltaMira Press.

O’Sullivan, D., & Unwin, D. (2010). Geographic Information Analysis: Second Edition. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Pollard, A.M. (1995). Why teach Heisenberg to archaeologists? Antiquity 69(263), 242–7.

Rivet, A.L.F., & Smith, C. (1979). The Place-names of Roman Britain. London: Batsford.

Roberts, B.K., & Wrathmell, S. (2000). An Atlas of Rural Settlement in England. London: English Heritage.

Southworth, M., & Southworth, S. (1982). Maps: an Illustrated Survey and Design Guide. Boston: New York Graphic Society / Little Brown.

Sturt, F. (2006). Local knowledge is required: a rhythm analytical approach to the late Mesolithic and early Neolithic of the East Anglian Fenland, UK. Journal of Maritime Archaeology 1(2), 119–39.

Sturt, F., Garrow, D., & Bradley, S. (2013). New models of North West European Holocene palaeogeography and inundation. Journal of Archaeological Science 40(11), 3963–3976.

Tufte, E.R. (2001). The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. 2nd edition. Cheshire, Conn: Graphics Press.

Wheatley, D. (2000). Spatial technology and archaeological theory revisited. In Lockyear, K., T.J.T. Sly and V. Mihăilescu-Bîrliba (Eds.) CAA96. Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology. BAR International Series 845. Oxford: Archaeopress, 123–131.

Wood, D. (2003). Cartography is dead (thank God!). Cartographic Perspectives 45, 4–7.

Yarrow, T. (2006). Perspective matters: traversing scale through archaeological practice. In: Lock & Molyneaux 2006a, 77–88.